One overlooked consequence of the lawlessness in Somalia in recent months has been the stream of refugees making their way across the Gulf of Aden northwards towards Yemen.

It is an extremely perilous journey, as this report from Reuters shows. The irony is that the Yemeni government was supplied with better coastguard vessels by the US government after the USS Cole attack in 2000.

Early reports have shown that those 'boat people' who survive the trip face difficult circumstances in Yemen. Their Arabic dialect is very different from Yemeni Arabic, meaning that they cannot easily find work and there is insufficient aid to help them. Yemen, for various reasons I covered a while back, is the poorest country in the Middle East.

Friday, December 29, 2006

The dangerous voyage to Yemen

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Not in the national interest

Sunday, December 17, 2006

Jordan coup averted?

A friend has just returned from a visit to the Middle East having heard a rumour from several sources that King Abdullah of Jordan has averted a coup. Apparently he has made a one-off payment to civil servants and the army in an effort to head off dissatisfaction.

Up until now Jordan has enjoyed the reputation (helped by an impressive security apparatus) of being one of the region's most stable regimes. Interestingly though, it seemed to me when I visited Amman late in 2004, that the new king probably did not enjoy the support that his father did. Throughout the capital were banners depicting a smiling Abdullah together with his equally cheery late father Hussein. Their message seemed to be "You liked me - now like my son".

However, like many other countries, Jordan has been destabilised by an influx of Palestinian refugees. Moreover, both Jordan and neighbouring Syria are having to cope with large numbers of refugees who had fled Iraq. If the rumours of the coup are true, they may help explain the tone of Abdullah's recent warning of civil war in the region. Whatever, the pressures of migration forced by the civil war in Iraq are likely to test the foundations of the states to the west, possibly to destruction.

Thursday, December 14, 2006

The answer is trade

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

A force to be reckoned with

It's now been twelve days since crowds massed outside the Lebanese Prime Minister, Fuad Siniora's office in Beirut, the Ottoman Saray, to demand his resignation. Hezbollah, which has stage-managed this confrontation from the start, has cleverly turned it into a tug-of-war between itself and the Lebanese and western governments, whose vocal support for Siniora has easily been portrayed as interference. The more the western governments now back Siniora, the more he looks like their puppet and is bound to fall.

It is hard to believe that Hezbollah would have had the power or confidence to orchestrate this uproar if the war this summer had not happened. Israel's invasion of southern Lebanon this summer was sparked by Hezbollah's ill-advised snatch of two Israeli soldiers patrolling near the border, inside Israel. Hezbollah's aggressive defence of Lebanon, in the face of US and British support for Israel and silence over the civilian casualties in Lebanon, has won it widespread support, not just from its Shia base, but from other Lebanese, including Christians, and beyond. When he visited Damascus this summer my friend Richard Spring was struck by the Hezbollah flags he saw flying in the Christian quarter of the old city. The solidarity Hezbollah has generated is formidable.

It is a mistake to see Hezbollah simply as an agent of the Syrians or Iranians. Sure, Hezbollah could not survive without their backing. But Hezbollah is also satisfying a long-held appetite in Lebanon for Arab, and latterly Lebanese, independence. In 1884 the political activist Jamal al-din al-Afghani (bear with me here) who opposed European colonisation of the Islamic world sent more copies of his influential periodical Al-Urwa al-Wuthqa to Beirut than any other Middle Eastern city save Cairo, where he was based. The Ottomans knew that Beirut was a hotbed of Arab nationalist feeling. In May 1916 they hanged 14 nationalists in Beirut - twice as many as in Damascus, as a warning. But Ottoman rule ended two years later, helped considerably by Arab opposition. While Hezbollah can portray itself - with some justification - as the guardian of Lebanese independence it is a political force to be reckoned with.

Monday, December 11, 2006

A side-effect of nuclear know-how

The news that the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council have announced their view that they have a 'right to possess nuclear technology for peaceful purposes' is no doubt a reaction to Iran's pursuit of nuclear weapons, although they deny it. A happy side-effect for the countries involved is that by developing nuclear technology they will effectively thwart outside efforts to encourage democracy within their borders.

If the GCC countries develop nuclear weapons, western governments will have a powerful interest in maintaining their undemocratic status quo, since Islamist parties frequently form the only opposition in these countries. In the short-run pursuing stability will be the west's only option, but this will only increase the problems in the Middle East long-term.

Sunday, December 10, 2006

The perils of pilgrimage

News that two British Muslim pilgrims have died in a coach crash while driving between Medina and Mecca is a sad reminder that even today the Muslim pilgrimage, the Hajj, continues to have its dangers. But these are slight compared to the risks one hundred years ago, before the train and plane made getting to the Hijaz to fulfil this once-in-a-lifetime demand of Islam very much more easy.

On her visit to Syria in 1905 the British traveller Gertrude Bell asked her guide about the hardships pilgrims faced on their way to Mecca. 'By the face of God! they suffer,' he answered: 'Ten marches from Maan [in sourthern Jordan] to Medain Salih, then from there to Medina and ten from Medina to Mecca, and the last ten are the worst, for the Sharif of Mecca and the Arab tribes plot together, and the Arabs rob the pilgrims and share the booty with the Sharif. Nor are the marches like the marches of gentlefolk when they travel, for sometimes there are fifteen hours between water and water, and sometimes twenty, and the last march into Mecca is thirty hours.' And he was less than complementary about the fortified caravanserai, or hostels, at which the pilgrims stayed along the route. 'Every fort is like a prison', he said. (The Desert and the Sown, New York 1907, p.239)

Saturday, December 09, 2006

Britain loses major ally in Helmand

The Times reports that the Governor of Helmand, Mohammed Daoud, has been sacked by President Karzai. The reasons for his dismissal are far from clear.

Engineer Daoud was appointed with strong British backing in January. He is seen as honest and not involved in drugs in a part of the world where both qualities are unusual commodities. He was also an outsider with no close link to any of the local tribes. Until a replacement is found the acting governor will be Daoud's deputy, Amir Muhammad Akhunzada, who could not be more different. One source quoted in The Times said: 'For the moment and before a new governor is named, the governor of Helmand is a drug-dealing warlord who was banned from the elections by the UN for keeping a militia and his connection to narcotics, and with whom the British have said they cannot work. Nice.'

Daoud had backed efforts to eradicate next year's poppy crop which is likely to equal or exceed this year's record-breaker, and the decision to remove him raises some awkward questions about President Karzai's priorities. Moreover, will the local peace agreements which Daoud negotiated hold?

Friday, December 08, 2006

Spot the difference

Some revealing semantics at the Bush-Blair press conference yesterday.

George Bush: 'I also believe we're going to succeed. I believe we'll prevail. Not only do I know how important it is to prevail, I believe we will prevail.'

Tony Blair: 'I am sure that it is possible to resolve this [the situation in Iraq] and I also do believe that if we do, then it would send a signal of massive symbolic power across the world.' [My emphasis]

'If' and 'would', Prime Minister? Surely 'When' and 'will'?

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Too late

A lot has already been written on the Iraq Study Group's thoughtful report, published yesterday. The report is an honest appreciation of the crisis in Iraq made all the more stark by the contrast of its tone and depth with the hallucinatory quality of previous statements on the prospects for Iraq made by politicians on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yet the report still has a slightly otherworldly feel to it. Its recommendations - external diplomatic initiatives designed to involve neighbouring countries which have a significant stake in Iraq's future, and internal efforts to achieve national reconciliation - all sound sensible yet still imply that the United States and legislation can play a role which events so far simply do not support. I cannot see Iran and Syria sitting down around a table at a meeting organised by the US government. The easiest way to persuade Iran and Syria to engage themselves would be for the US to withdraw, yet the report rules out this drastic option. After Recommendation 23 the report sets out a series of milestones involving legislation to achieve, for example, amnesties and Iraqi control of its army by the end of next year. And yet earlier, the report clearly states that the army is already divided along regional (and therefore probably sectarian) lines and that the government has favoured Shia over Sunni areas. If that is the consequence of democracy, it is hard to see how any legislation enacted within the Baghdad green zone will have any tangible effect beyond it. With the violence increasing every week and the country's institutions corrupted seemingly beyond repair, I suspect that the report's suggestions have simply come too late.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Hezbollah's ancestors?

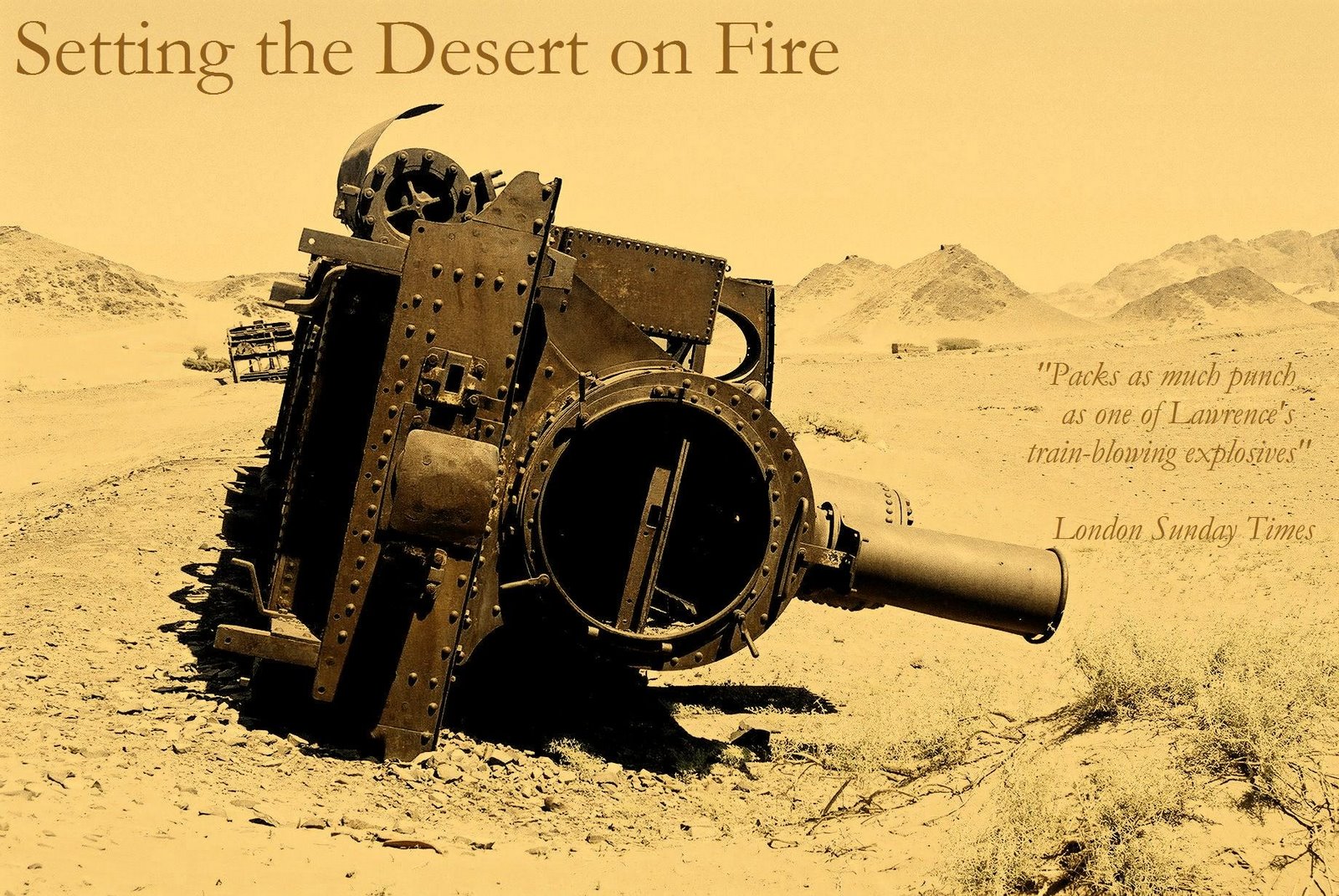

I'm currently revising my book for the U.S. edition which will be published by WW Norton during next year.

I'm at the stage where Lawrence sets out on a long, behind-the-lines trek into Syria and Lebanon in June 1917. During this mission, he stopped in the Bekaa valley in what is now Lebanon to dynamite a railway bridge. ‘The noise of dynamite explosions we find everywhere the most effective propagandist measure possible’, he wrote afterwards., for the demolitions apparently triggered a revolt by the local Metawala tribesmen. Whether Lawrence did what he claimed has been disputed since: intelligence reports from both the British and the French of an uprising in the area are the strongest evidence there is that he was telling the truth.

The Shiite Metawala were concentrated in southern Lebanon. They were, according to Gertrude Bell ‘an unorthodox sect of Islam’ which had ‘a very special reputation for fanaticism and ignorance’ (The Desert and the Sown, New York 1907, p.160.) I can find little evidence of them today, save for the fact that a village in northern Israel, which was at the centre of the war earlier this summer, is named Metulla. Is there a connection, I wonder. And are the Metawala the ancestors of the modern Hezbollah?

Saturday, December 02, 2006

Whatever happened to the Popular Front?

Seth Wikas of the Washington Institute has produced a handy short guide to the various opposition groups in Syria that the US government is now apparently talking to. It is not an appetising menu.

The Iraq Study Group, whose report is imminent, is expected to advocate engagement with both the Syrian and Iranian regimes. However, the Bush administration's combined output on these countries - labelling Iran as part of the axis of evil and Syria as an associate member - will make it hard for President Bush to accept this approach without implicitly acknowledging that his foreign policy since 9/11 has been a disaster.

The alternative, then, is engagement with the opposition groups in Syria and the exiled Syrian diaspora. If memories are too short in the US administration to remember the outcome of this approach in Iraq (where they backed Ahmed Chalabi) they might sit down one evening and watch the hilarious People's Front of Judea exchange in the Life of Brian which ends with Francis asking "Whatever happened to the Popular Front, Reg?" Reg: "He's over there." Chorus: "SPLITTER!"

Friday, December 01, 2006

Look who's adopting guerrilla tactics in Afghanistan

Reuters has a fascinating report today. It shows how the British have learned from the earlier months of their deployment to Helmand, Afghanistan, by adopting guerrilla tactics to target the Taliban along the fertile Helmand river. Previously the Taliban had taken advantage of the fact that the British were obliged to defend a small number of widely spaced 'platoon houses' in the major towns of northern Helmand. Although it is an implicit acknowledgement that the British forces in southern Afghanistan are overstretched, the Royal Marines' approach may turn the tables.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Don't buy a goat this Christmas

'Buy a goat and provide improved nutrition and income generation for a family in Niger or Malawi' - UNICEF. 'Goats: packed full of nourishing delicious milk' - Action Aid. 'These loveable animals are not only an essential source of nutritious milk for an African family, but thanks to a revolving goat project families can breed them to generate income to pay for their child's education - and release themselves from poverty forever' - Practical Action. Goats were Oxfam's biggest seller last year. Everyone wants you to buy a goat this Christmas.

Sounds great doesn't it? Work off your Christmas guilt and hangover by buying a goat for a poor family in Africa or the Middle East. A goat which reproduces, creating yet more goats. But it's a mad idea.

Earlier this year I went to Ethiopia. I was astonished one day to see a goat that had managed to climb a tree, which already looked like wicker. It was eating the last green shoots. Goats eat everything. They turn pasture into desert. In the Simien Mountains, where I was, the earth is like brown talcum powder which blows away when you tread on it. Oxfam, in its defence, says that it 'only provides livestock to communities where livestock keeping is an essential or traditional way of life, and appropriate to the local environment.' But 'It's Traditional' is second-rate thinking. Traditions die out when the people who follow them die out: you only have to look at Easter Island for proof of that, where the people cut down the trees to make logs to roll the statues into place. Charities don't exist to support tradition, because tradition isn't always best. They are there to change and improve.

The charities offer other gifts. Sanitation is still the greatest problem in the third world, though pit lavatories are not fluffy or 'loveable' (a laughable idea for anyone who has watched an Arab thwacking a donkey with a stick). Just please don't buy a goat.

Monday, November 27, 2006

Why are we in Mesopotamia?

Listening to the British Defence Secretary Des Browne's comment today that "I can tell you that by the end of next year I expect numbers of British forces in Iraq to be significantly lower by a matter of thousands", reminded me of the words of an earlier politician. He wrote on 1st January 1921 how "I feel some misgivings about the political consequence to myself of taking on my shoulders the burden and the odium of the Mesopotamia entanglement". If you haven't already guessed, or recognised the quote, it was the highly ambitious Winston Churchill. He had just been appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies, with responsibility for the Middle East. Worried his reputation might be irrevocably damaged by the problems he had been asked to deal with, he would spend the next three months desperately searching for a way to cut Britain's military commitment in Iraq. It looks like Des Browne is doing much the same thing - spurred, I suspect, by the chastening mid-term election results in the United States.

In 1921 Britain ran Mesopotamia, as it then was, as a result of its determination to protect its oil fields in southern Persia during the First World War. In a classic example of mission creep, this defence had ended with the British capturing Baghdad in 1917. As more oil was discovered and its importance in powering the Royal Navy was recognised, they were reluctant to give up their new possession. But the post-war administration of the country, which largely excluded local Arabs, was inept. "I regard the situation in Mesopotamia as disquieting, and if we do not mend our ways, will expect revolt there about March next", TE Lawrence wrote in September 1919. Eight weeks later than he predicted, in May 1920 violence erupted in Iraq. Lawrence would become perhaps the most vocal critic of the government in the months that followed, arguing that Britain should stand back and allow the Arabs to run the country for themselves. "What is required", he wrote in an article in the Observer, "is a tearing up of what we have done, and beginning again on advisory lines." His position was a popular one. A further, famous article he wrote for the Sunday Times was supported by a leader in the paper which asked: "Why are we in Mesopotamia? Uninformative statements which have been issued by the Government convey the impression that officialdom is bewildered and anxious rather to conceal its blunders than to mend them. But they can be concealed no longer…"

"We have not got a single friend in the press upon the subject", Churchill wrote about the crisis in Iraq in 1920. He regretted “pouring armies and treasure into these thankless deserts”. When he was then given the task of tearing up past policy, it was a unpalatable job which has a familiar ring today.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Syria's alliance with Iran

Just how solid is Syria’s alliance with Iran – the partnership that Britain and the United States are now seemingly trying to break up? In my view, not very.

What unites Syria with Iran is its concern about the threat posed by their common neighbour, Iraq, the country carved from the Ottoman Empire by Winston Churchill and TE Lawrence in 1921. Iraq was made the shape it is to connect the northern oil fields around Mosul with the Gulf port of Basra in the south, and to stop the French (who then ran Syria) from meddling in the Arabian peninsula: hence Iraq's western border with Jordan ensures that Syria and Saudi Arabia do not touch. But, thus defined, Iraq combined a highly combustible mix of religious and ethnic groups which has proved a nightmare for its rulers ever since. The first, the British-backed King Feisal, complained twelve years after he was crowned that ‘There is still – and I say this with a heart of sorrow – no Iraqi people but unimaginable masses of human beings, devoid of any patriotic idea, imbued with religious traditions and absurdities connected by no common tie, giving ear to evil, prone to anarchy and perpetually ready to rise against any government whatever.’

Worried about relying on Iraq for oil, in 1982 Syria negotiated an oil-for-phosphates deal with Iran and then, with its energy supplies assured, cut its ties with Iraq. But Syria and Iran are very different: Syria is a secular dictatorship in which religious fundamentalism has been brutally crushed; Iran a theocracy with ambitions to reclaim a broad swathe of the Middle East, including parts of Iraq and Afghanistan, which it sees as historically Iranian. The population of Syria is largely Sunni, though significant to understanding the regime’s commitment to religious tolerance is the fact that the President, Bashar Assad, comes from the tiny Alawite minority. The people of Iran on the other hand, are mainly Shia. Each country has secretly backed its co-religionists in Iraq, so that Sunni and Shia are now engaged in a ferocious civil war against each other. It is an odd way for two supposed allies to behave.

Iran’s motives for supporting the Iraqi Shias were probably territorial: it would like to extend Iran westwards to the bank of the river Tigris. Syria’s motivation in backing the Sunnis was rather different. Thrown in with Iran and North Korea as an associate member of the 'Axis of Evil' from mid-2002, and fearing it might be next on the United States’ list of targets, Syria armed the Sunnis in Iraq to bog the American invasion down. To understand the Syrians' concerns, it is worth recalling Lawrence's opinion that Syria is 'a country peculiarly and historically indefensible against attack from the east'.

Viewed cold-heartedly, the Syrian policy has been a short-term success. More coalition troops have died in Iraq's western Anbar province, which borders Syria, than in any other part of Iraq and the Americans’ enthusiasm to take on Syria next has now evaporated. But when the coalition leaves, Syria's proxy war becomes a highly dangerous policy, for the Syrian border with Iraq is very porous and the violence in Baghdad is closer than Damascus would like. And the sectarian violence that will probably engulf Iraq following a US withdrawal will pit Syria directly against its supposed ally, Iran. Meanwhile, Iran's claim that it will use its nuclear weapons against Israel, which would surely leave Jerusalem, a holy Muslim city, uninhabitable sits oddly with its attempt to orchestrate anti-western opinion throughout the mostly Sunni Islamic world.

It is the realisation that a precipitate American and British withdrawal from Iraq would leave them in a confrontation with the Iranians that is encouraging the Syrians to reconsider their support for the insurgents. This helps explain the Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Moualem’s visit to Baghdad last week, and the reopening of diplomatic ties between the two countries for the first time since 1982. While he was in Baghdad, Moualem signed an agreement agreeing that American troops should remain in Iraq. And that shows just how vulnerable the Syrian position is.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Wild pigs

It's frequently said about Spain - where I've just spent a few days - that it is still possible to see the Moorish legacy on the country, more than five hundred years after the Muslim King of Granada finally surrendered to Ferdinand and Isabella on 2 January 1492, completing the reconquista. That influence is obvious in the architecture and, as I discovered while perusing a menu, in the language of the food.

As anyone who has visited will know, the Spanish are mad about ham. There are dozens of types: cured for different lengths of time, with different smoke, and so on. But what caught my eye was the Spanish word for wild pig, which is 'Jabali'. It is a word which rang a bell from my travels in the Middle East on the trail of TE Lawrence, for Jabal in Arabic means mountain. Devout Muslims do not eat ham today: but I wonder whether that was always the case in Spain?

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Al Jazeera goes live in English

The infamous Arabic satellite news channel, Al Jazeera, launched its English language service today to an estimated 80 million homes around the world. Its aim, its director-general says, is to try to reverse the flow of information which currently runs from north to south. It will be interesting to see what effect it has on other broadcasters’ coverage of international news.

Like the BBC, Al Jazeera – ‘The Island’ in Arabic – has made a virtue of its impartiality. As anyone who has visited the Arab world will know, the enormous, rusty satellite dishes on almost every roof testify to a yearning everywhere for independent news which is not satisfied by the turgid daily gobbets from government news outlets. See this scintillating item from the official Syrian news agency, SANA, today if you remain to be convinced.

As the BBC cuts back its short wave radio World Service – and weirdly hopes that its audience around the world can tune in via the internet – there may well be space for Al Jazeera. But whether it can cover the world as it claims it wants to “from the south”, will all boil down to budget. I saw Jon Snow, the journalist and Channel 4 News anchor, speak last year on just this subject, and he reminded the audience that it is far cheaper to broadcast live from the USA than it is to commission a report from Darfur, say, in western Sudan, where there is a genocide going largely unreported. The worst example of the consequences of this, the one that made my blood boil, was the way in which the BBC devoted an entire half-hour evening news bulletin to the verdicts in the Michael Jackson trial in June last year.

Perhaps Al Jazeera will force the BBC to follow more expensive foreign stories. I hope so. But in these cash-strapped times, the frequently trivial rubbish breaking in the developed world looks likely to continue to trump those genuine news stories emerging from the more dangerous and remote elsewhere.

Monday, November 13, 2006

The struggle over Siachen

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Saddam the martyr?

I've spent the last few days pondering what impact hanging Saddam Hussein will have. It looks highly unlikely to curb the mounting violence in Iraq. The authorities there (if such a word applies amid such anarchy) feared his death sentence would have the opposite effect. The Shia, for whom Iraqi television is evidently much too dull, want the execution broadcast live. Will it, as some worry, create a martyr? I suspect not, though it is posterity, rather than the executioner, that determines martyrdom.

The most famous Arab martyrs are commemorated in the present names of two public squares in Beirut and Damascus. In 1916 they were known, respectively, as the Burj and the Marjeh. Today, for the events of 6 May that year, both are known as Martyrs' Square. The men hanged there in public early on that date had been sentenced to death for treason against the ruling Ottoman regime. Their crime was to have asked the French for assistance with their cause, and it was the letters they naively sent the French consul which were found when he abandoned his office in 1914 that condemned them. They represented an increasingly self-confident Arab intelligentsia: besides an army officer, a newspaper proprietor, magistrate, barrister, and several local politicians were executed. They were successful people, frustrated by the Arabs' second class status within the Ottoman Empire at that time. One of them died calling on 'the civilised nations of the world' to help them achieve 'our independence and freedom'.

Men less like Saddam you would find it hard to find.

Friday, November 03, 2006

2007 poppy harvest may match record

Next year's opium harvest in Afghanistan may match this year's record levels, Associated Press quotes an anonymous US official predicting. This crop this year was an estimated 6,000 tonnes, producing 600 tonnes of heroin. The planting of next year's crop has now begun.

The official directly linked the size of the harvest with Afghan government's loss of control of the southern provinces of the country, where opium poppy is mainly grown. "We've actually lost a lot of governance in a number of districts in Kandahar, Helmand, and Uruzgan, where the government isn't flying the flag," the official said. "You've got Taliban there that are more in control than the government."

When it is harvested next spring, the size of next year's crop compared to this year's will be a clear indicator of whether NATO is succeeding in bringing greater stability to Afghanistan.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Boris recants

You can see a perfect example of the sea-change I wrote about two days ago from the brilliant commentator and Conservative MP Boris Johnson in today's Daily Telegraph. Johnson is the shambolic-looking but razor-brained voice of the Telegraph and I would be willing to bet that more readers buy the paper for his Thursday column than for any other single reason (except, probably, the cartoonist Matt). Here he is today completing a u-turn on Iraq:

"It is now commonplace for people like me, who supported the war, to say that we "did the right thing" but that it had mysteriously "turned out wrong". This is intellectually vacuous. It is like saying British strategy for July 1, 1916 was perfect, but let down by faulty execution. The thing was a disaster from the moment we invaded, and it wasn't poor old Rumsfeld's fault for failing to send in enough troops, or failing to do more "planning" for the post-war. No quantity of troops could have prevented this catastrophe; and the dreadful thing is that I think Saddam knew it."

"As long as we are there [in Iraq], the terrorists know that they can maximise the damage to Bush and Blair by blowing up our troops, and so we incite the very violence we are trying to quell. We need to plan for withdrawal, and we need to understand why, why, why we were so mad as to attack Iraq without working out the consequences."

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

The road to Damascus

The move comes after British MP Richard Spring's prediction in the Guardian last week that Britain would open talks with the Syrian government.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

More gung-ho than the government

If the British government loses a parliamentary motion tonight it will be obliged to call a public enquiry into the conduct of the Iraq war. Faced with this unappealling prospect, it has resorted to a hysterical attack to try to stop the rot, denouncing its Conservative opponents - who can probably tip the balance - as traitors. The Sun reports the Tony Blair's spokesman as saying: 'We have an enemy looking for any sign of weakness at all, any sign of a loss of resolution or determination to see this job through.'

Any mujahideen with access to the internet - and the signs are there are plenty of them - would see from a cursory reading of the British press that there are plenty of 'signs of weakness' already. Every recent opinion poll in the British papers shows that public support to 'see this job through' is rapidly waning. The pro-war papers themselves have been trimming to chime with their readers' more sceptical views. And when the head of the Army says that the British army should 'get ourselves out sometime soon because our presence exacerbates the security problems' caused by intervention and Mr Blair says he agrees, then the government's attack today looks ridiculous.

The underlying problem is that the Government has relied all the way on Conservative support for its Iraq policy. Its claims on weapons of mass destruction - which turned out to be nonsense - enjoyed an easy ride in Parliament because of the Conservatives' readiness to believe them. During the war that followed, the Conservatives have been more gung-ho than the government. Had they been more circumspect in their support from the outset, they would be way ahead in the polls by now.

That is changing. For the Conservatives, the appetising prospect of winning votes finally seems to have outweighed the trenchant support for the war they have espoused until now. That is why the government is so worried tonight.

Monday, October 30, 2006

The first cuckoo of spring?

Lots of interesting information in the media over the weekend on the situation in Afghanistan. The Independent on Sunday reports that British soldiers have now stopped patrolling in the regional capital Lashkar Gah because the threat from suicide bombers is too great. A marine was killed in a similar bombing in the town ten days ago. It also suggests that the incoming Royal Marines Commando force, which has taken over from the Parachute Regiment, does not share the Paras' view that the Taliban have been tactically beaten. And the Royal Marines' view is that the aggressive defence forced on the Paras has been counter-productive. 'For every Taliban you kill', the 42 Commando spokesman is quoted saying, 'you recruit three or four more' . The view has not filtered down to the soldiers now confined to Camp Bastion, the British forces' base in the province. 'What we really want to be doing is fighting' one bored soldier tells the Mail on Sunday.

There has been less fighting recently in northern Helmand - possibly because of Ramadan or the poppy-planting season - but British troops guarding the hydro-electric dam across the river Helmand at Kajaki continue to be attacked. A Guardian article last week suggested that it was a botched special forces operation which precipitated the violence seen earlier this summer.

A fascinating question and answer session with David Loyn, who reported on the Taliban, last week (the report was the target of some kneejerk criticism) sheds more light on the complexity of the situation and helps explain why the Taliban enjoy the support they do.

Finally, Lord Guthrie, the former Chief of Defence Staff, is interviewed in the Observer. He reveals his scepticism of the chances of success in Afghanistan with the current levels of men deployed and, more damagingly, rightly questions whether Tony Blair's offer of 'whatever equipment' is needed can be delivered. And he makes a none too subtle swipe at John Reid, the former Defence Secretary who ill-advisedly expressed his hope that British troops would leave Afghanistan without firing a shot. 'Anyone who thought this was going to be a picnic in Afghanistan - anyone who had read any history, anyone who knew the Afghans, or had seen the terrain, anyone who had thought about the Taliban resurgence, anyone who understood what was going on across the border in Baluchistan and Waziristan [should have known] - to launch the British army in with the numbers there are, while we're still going on in Iraq is cuckoo.'

Friday, October 27, 2006

Oxford seminar

The seminar kicks off at 5.15pm, at the Middle East Centre, 68 Woodstock Road, Oxford.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Insight or propaganda?

Last night's Newsnight piece on the Taliban in Helmand, Afghanistan, was a piece of superb and brave journalism by the war correspondent David Loyn. Loyn risked his life - or at least put a huge degree of trust in the Pashtun honour code - to go behind the lines in Helmand and investigate what is going on. Last month the outgoing British commander Brigadier Ed Butler said that the Taliban had been tactically defeated. Loyn's report suggested otherwise. The Taliban are free-range, well armed (with captured night vision goggles and .50 cal machine guns among other things) and enjoy some support from local people who are aggravated by corruption, which commonly takes the form of illegal roadblocks charging 'tolls'.

Today, various Conservative politicians in Britain are getting hot under the collar about the report. Julian Lewis said it was 'unalloyed Taliban propaganda', while Liam Fox described it as 'obscene'. But the Tories should stop trying to do the government's job for it, and start shouting louder for the reinforcements the British need to send to Afghanistan, if they are to have a hope to achieving what they want to. What the report so clearly showed was that the government is wrong to claim that it is winning in Helmand, and as the opposition the Conservatives should be asking why that is.

What the report did not go into was the Taliban's claim to have outlawed opium production when they were in power. Up to a point Lord Copper. The Taliban earned duty from exports of the drug and did not want over-supply to the value of the commodity and so the income they derived from it. Money, not religion was the motive for the ban, and it would have been good to hear that aired.

Monday, October 23, 2006

The Hijaz and Helmand

Exactly ninety years ago this month, a short, fair-haired young man with piercing blue eyes stepped off a launch onto the quayside at Jeddah on the eastern shore of the Red Sea. The port stood at the edge of the Hijaz, the formidable chain of serrated ochre mountains that hid Mecca and Medina, the holiest cities in the Muslim world. ‘The heat of Arabia’ he would later write, ‘came out like a drawn sword and struck us speechless.’ Arabia would make him famous, for his name was TE Lawrence.

Lawrence had arrived in Arabia to rescue a tribal uprising, backed by Britain, that had expelled the Turks from Mecca but which had now run out of steam. The Turks looked set to retake the holy city and seemingly, the easiest way to stop that happening would have been to send the tribesmen British reinforcements. But British troops were scarce, and deploying them to such a sensitive area was deemed unwise. Lawrence was forced, through desperation, to consider other tactics. ‘The Hijaz war is one of dervishes against regular troops’, he quickly realised, ‘and we are on the side of the dervishes.’ This was revolutionary and provocative. One senior officer, a veteran professional soldier who with Kitchener in the Sudan had defeated the dervishes, called Lawrence ‘a bumptious young ass’ who ‘needed kicking, and kicking hard at that.’

But Lawrence had a point. A classic military manual of the era, Small Wars, contained a timeless warning for its readers: ‘Guerrilla warfare is what the regular armies always have to dread, and when this is directed by a leader with a genius for war, an effective campaign becomes well-nigh impossible.’

Lawrence was to prove this maxim right again. He advocated sending a handful of British advisers to direct the Bedu, armed with copious quantities of gold and dynamite. ‘This show is splendid’ he wrote a short time later to a colleague who was about to join him. ‘You cannot imagine greater fun for us, greater fury and vexation for the Turks’. It was frustrating, because as Lawrence commented after the war, ‘Many Turks on our front had no chance all the war to fire on us’.

Over the next two years Lawrence honed his unorthodox strategy, with results can still be seen today. Blown-up locomotives, half-sunk in the desert sand. Lonely stations pock-marked with bullet holes. Graves with jagged shards of rock for headstones. A handful of daring British officers and their Bedu helpers pinned down 11,000 Turkish soldiers,who never did re-enter Mecca. The Hijaz Railway never worked again and today its track has vanished altogether.

When Lawrence looked back on his own exploits afterwards, he believed that the Turks would have needed 600,000 men in all, at least twenty soldiers in fortified posts every four square miles, to have defeated the insurgency. That was the tactic that had beaten the Boers in southern Africa and the Mohmand tribesmen on the North-West Frontier. The British were not squeamish about how they subdued the Mohmands, great-grandfathers of the Taliban. The blockhouses they built at eight hundred yard intervals were linked by electric fences that, the local governor reported, had killed ‘two Mohmands, six dogs, seven jackals and one cat’.

Seven hundred miles to the south-west today, across the border in Afghanistan, British troops are again trying to deal with an insurgency. The heat and the landscape of Helmand province, southern Afghanistan, have strong similarities with the Hijaz, and the tactics the Taliban are now employing are eerily familiar. ‘They didn’t come out and fight anymore’, one young soldier said: ‘I didn’t have to fire a shot’. Yet in this dusty region, which is a quarter the size of the Hijaz, Britain has deployed barely 5,000 men in isolated pockets: nowhere near enough to achieve the security they were tasked with achieving, sent by a government that, like the Turks in Arabia ninety years ago, refuses to admit defeat.

As Lawrence proved, too few troops, defending too large an area is a vulnerable combination. The British army knows it. It has now started to withdraw troops from the isolated outposts it occupied around the province earlier this summer under pressure from the energetic local governor, Mohammed Daoud. Daoud’s strategy is the right one – there can be no significant reconstruction without a great improvement of security across the province – but the British government has not supplied the resources to sustain it. As a consequence, British soldiers have been too thinly spread and, just as the Turkish railway was an easy target for Lawrence, their own lifeline to the outside world – by helicopter – is very exposed to Taliban attack.

Britain’s prime minister, Tony Blair, has offered the troops in Helmand ‘whatever’ equipment they need. But by Lawrence’s calculation, it is thousands more men that are required, up and down the towns and villages of the Helmand river, to make conditions safe enough for aid work. Without those reinforcements, the reconstruction effort – designed to wean the local economy off opium production which, it is believed, helps fund Islamist terrorism – is doomed to fail. The situation is too dangerous for aid workers at the moment, and so far, just two bazaars have been rebuilt. Meanwhile an estimated 70,000 children cannot get an education because Taliban intimidation has closed their schools.

Security provides the foundation for reconstruction and reconstruction is crucial for winning the battle for hearts and minds which will defeat the Taliban. Here the forceful British tactics seen so far are not succeeding. ‘The British brought nothing but fighting’, complained the turbaned elders of one town. ‘Women have been killed. Children have been killed’, mourned one man in another. As Lawrence noted, his own success depended on ‘a friendly population, of which some two in the hundred were active, and the rest quietly sympathetic to the point of not betraying the movements of the minority.’ Much is made of Lawrence’s leadership. But the truth is that the alliances he formed were bought with gold.

Ninety years on, Lawrence’s advice is simple and still relevant. Many more men and much more money are both needed if the British are to have a hope of winning in Helmand.

Friday, October 20, 2006

Food fight

As my good friend and blogger Tom observes, the Middle East has a new front.

Outside his supermarket he found campaigners urging him to Boycott Israel. In my local supermarket, that would be difficult. The only thing I can think of that comes from Israel, is rosemary: something which, incidentally, grows perfectly well in Britain. But it's a growing trend. A Palestinian olive oil producer makes great play of its political credentials. The Israelis, meanwhile, are fighting back. But a lot of the links don't seem to work. Who will win the food fight?

Friday, October 13, 2006

A crime to deny the Armenian genocide?

The French Parliament voted yesterday to make it a crime to deny the Armenian genocide committed by the Turks between 1915-17. The killings happened during the First World War and while the Turkish government continues, rather half-heartedly, to pretend they never happened, or at least were not a genocide, the evidence is compelling. At first sight the Parliament's vote might seem a good idea. The French Armenian community welcomed it, after all.

The French Socialists who backed the vote, have interests closer to home, and much less noble. They are trying to win anti-Turkish feeling, which is already strong in France. The French, who consider themselves the architects of the European Union, generally do not support Turkey's hope of joining the club they feel they founded. And yet to exclude Turkey would only reinforce the divide between East and West, already so visible elsewhere. The socialists of course, also fear cheap Turkish labour taking jobs in France. where unemployment is obstinately high. This low motive, not high morality, lies behind the law.

Turkey's ongoing refusal to admit the killings were systematic is ridiculous, agreed. But far better to do what else happened yesterday and award the leading Turkish novelist and historian, Orhan Pamuk, the Nobel Prize for Literature. Pamuk has already publicly talked about the genocide, which is a crime in Turkey. But he is too famous to be imprisoned, and other novelists put on trial for doing the same have also been acquitted. This approach of praising the freedom of speech, and not a law which does the opposite, is the way to safeguard the truth.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

I've just watched a quite astonishing interview on the BBC's news analysis programme Newsnight, following on from the leaked document I covered earlier. In it, Sir John Kiszely, the director of the Defence Academy, a Ministry of Defence think-tank, tried to claim that what Newsnight had revealed was the "raw material" not a finished, polished view. Newsnight effectively rubbished that, but what was most interesting, was when Kiszely tried to fend off a question on whether the document was an accurate reflection of the current state of play in Iraq and Afghanistan, with the wonderful answer: “This is not an area of my expertise”. Sir John has served as the Senior British Military Representative in Iraq.

There's something odd about all this. Why, if Newsnight was so wrong, did it take the Defence Academy 12 days to rebut its allegations? And, if not in the two main areas of active British deployment, one of which he has served in, what is Sir John an expert in, then?

Thursday, October 05, 2006

The view from Helmand province, Afghanistan

There are some contradictory reports coming from Helmand province in Afghanistan, where British troops are deployed on a mission which was originally billed as a reconstruction effort designed to wean the local economy off the opium trade. Since then it has become clear that British troops are fighting a war so dangerous that it has largely gone unreported, except by the soldiers themselves.

The question is how that war is going.

Let's start with the view of Brigadier Ed Butler, the commander of the UK Task Force and 16 Air Assault Brigade, the unit which is about to finish its tour in the province. Reviewing the previous six months - which he described as a "war of attrition" - on 27 September he said: "I think we've won, we may not be quite there yet this year". He was referring to the tactical battle to defeat the Taliban. Butler also reported that "a secret deal" had "brought a halt to violence" in Musa Qala, a government outpost in northern Helmand.

Further revealing details about that secret deal have since emerged. "We were not going to be beaten by the Taliban in Musa Qala," the Daily Telegraph quoted Butler as saying, "but the threat to helicopters from very professional Taliban fighters and particularly mortar crews was becoming unacceptable. We couldn't guarantee that we weren't going to lose helicopters." Let alone the logistical problems losing a helicopter would cause (the British have only 6 Chinooks available at the moment), knowing that such a loss would cause significant political fallout in Britain, 16 Bde were compelled to conclude a deal, brokered by Afghan elders: the British won't shoot if the Taliban don't shoot at them. The elders are expected to persuade the Taliban not to attack - precisely the task of British troops, who were supposed to be protecting the reconstruction effort. The real reasons for the truce are 1) British forces are overstretched and underequipped and 2) having sold the mission to the public as a reconstruction effort British politicians do not believe that the public will tolerate casualties.

There is now a lull in the fighting, according to the British. "I fully acknowledge that we could be being duped; that the Taliban may be buying time to reconstitute and regenerate," Butler told the Daily Telegraph. "But every day that there is no fighting the power moves to the hands of the tribal elders who are turning to the government of Afghanistan for security and development." However, Tom Coghlan, the Telegraph reporter, came up with another, thought-provoking suggestion for the sudden lull in Taliban activity: a two weeks or so ago, the new opium poppy sowing season began.

In the meantime there are few signs that the wider, strategic battle for hearts and minds is being won. The UNHCR estimated this week that 90,000 Afghans have been displaced by the fighting in southern Afghanistan. And Reuters carried another interesting report about the Taliban's efforts to force schools in southern Afghanistan to close. It is a measure of just how deep the problem is that even the girl's schoool in the regional capital, Lashkar Gah, which is under British noses, has been threatened. The British have an uphill struggle ahead.

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Big deal

Another day, another intriguing leaked document. Today it's apparently from the Ministry of Defence who have since been trying to claim that the views in it are not government policy. Its author, whom the BBC will not name on security grounds, was first dismissed by the British government as a junior, then a middle ranking officer. Just now on the BBC's late evening analysis programme, Newsnight, it has been revealed that he was appointed by the Chief of the Defence Staff to liaise with the US government in the war on terror. So probably not that junior then.

Most reports on this document have concentrated on its claim that 'The War in Iraq...has acted as a recruiting sergeant for extremists from across the Muslim world.' Nothing terribly original in that.

What is interesting, is the admission, which I hadn't heard before, that the British have been trying to pull their troops out of Iraq. 'British Armed Forces are effectively held hostage in Iraq - following the failure of the deal being attempted by COS (Chief of Staff) to extricate UK Armed Forces from Iraq on the basis of 'doing Afghanistan' - and we are now fighting (and arguably losing or potentially losing) on two fronts.'

What was the 'deal' mentioned here. Who was it with? What were its terms? And why did it fail?

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Who is right?

Towards the end of his speech at his party's annual conference yesterday, Britain's Prime Minister Tony Blair turned to the threat of terrorism: "This terrorism isn't our fault," he said: "We didn't cause it. It's not the consequence of foreign policy." [My italics]

Later the same day, after sections of the secret National Intelligence Estimate on Trends in Global Terrorism were leaked, the US Government released fuller extracts of the report. It says:

"We assess that the Iraq jihad is shaping a new generation of terrorist leaders and operatives; perceived jihadist success there would inspire more fighters to continue the struggle elsewhere.

The Iraq conflict has become the "cause celebre" for jihadists, breeding a deep resentment of US involvement in the Muslim world and cultivating supporters for the global jihadist movement." [My italics again]

Who is right?

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

'An open and genuine contest' - EU

Yemen's President, Ali Abdullah Saleh, pictured right, ended up taking 77% of the vote in last week's elections - a percentage still in any dictator's comfort zone but a significant drop from the 96% he polled last time around. If he haemorrhages another 20% in the next seven years, the next election promises to be an interesting one.

What's interesting is that the EU monitors who observed the election have produced a contradictory preliminary statement which describes the election as 'an open and genuine contest', in one breath and then identified 'a number of important shortcomings' in the next. Apparently it's only observers from the United Arab Emirates (whose view matters, since the UAE is the most prominent supporter of Yemen's hope of joining the Gulf Cooperation Council) who have questioned the validity of the poll.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Quietly sympathetic

Support among Iraqi Sunnis for the insurgency has risen to record levels, according to a poll referred to on the evening BBC news in Britain last night. The survey, which was apparently sponsored by the US Department of Defense apparently indicated that 75% of Sunnis questioned now support the insurgency, up from 14% in 2003.

As TE Lawrence recognised 90 years ago, winning this broad tacit support is the key to success in guerrilla warfare. He wrote in Seven Pillars of Wisdom:

"... our rebellion had an unassailable base.... It had a sophisticated alien enemy, disposed as an army of occupation in an area greater than could be dominated effectively from fortified posts. It had a friendly population, of which some two in the hundred were active, and the rest quietly sympathetic to the point of not betraying the movements of the minority." (1935 edition, p.196)

Thursday, September 21, 2006

No change in Yemen

I'll be surprised if the ruling President Ali Abdullah Saleh ends up with anything less than 75% of the vote in the presidential election in Yemen.

I'll be surprised if the ruling President Ali Abdullah Saleh ends up with anything less than 75% of the vote in the presidential election in Yemen.

The government in Yemen controls TV and radio, and has done its best to intimidate the few independent journalists who try to report on the endemic corruption within the country. In previous elections voters have been under-age, or bussed in from other constituencies to vote the government back in. "We are not a democratic country", one opposition politician told me when I visited earlier this year, "We are trying to be." Still, if Saleh has won only 80%, that is a significant swing against him. But there is still a long, long way to go.

Yemen's most recent troubles started back in 1990. Yemenis used to work around the Middle East, but when Saleh backed Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait that year Yemen was ostracised by other Arab countries and Yemenis were forced to return home. Unemployment has ballooned since, the population is growing unsustainably, and the country's oil is running out. And, as a walk around the capital, Sanaa, confirms, the famous statistic that, in Yemen, guns outnumber people by a ratio of 3:1 seems quite possible. Angry young men with lots of guns is a combustible mix.

Western governments are alive to the dangers of an unstable Yemen. And it is under pressure from these governments that President Saleh has promised to embark on the much-needed economic reforms that Yemen needs. But in this, the poorest of Arab countries, a tentative step in this direction last year - a cut in the petrol subsidy - sparked outrage and riots that led to many deaths. Most of the cut was rapidly reinstated. And his political party, the GPC, seems less convinced about the need for reform. I listened to the party's deputy general secretary complain that the opposition (who are massively outnumbered in a parliament which, in any case, has no real powers) were continually telling lies. "They always say that everything is black", he said. But if anything, 'black' is an understatement.