A court has given permission for the body of Sir Mark Sykes to be exhumed, the BBC reports. Sykes died, in great pain, from influenza in Paris on 16 February 1919 and was buried in a lead-lined coffin at his family home at Sledmere in Yorkshire. Scientists hope that the virus that killed him might be preserved inside the coffin, and that samples of it may help them create drugs to fight a future flu outbreak.

Even before he died, Sykes was a controversial figure. “He was a worried, anxious man. That was the cause of his death,” suggested the then Prime Minister David Lloyd George. “He had no reserves of energy. He was responsible for the agreement which is causing us all the trouble with the French”.

The agreement was the Sykes-Picot agreement, which was negotiated by Sykes with Francois Georges-Picot over the winter of 1915-16. Britain initiated discussions to allay French suspicions about their policy in the Middle East. The agreement divided the near Middle East along a diagonal line, ‘from the “e” in Acre to the last “k” in Kirkuk,’ to quote the words Sykes used as he sliced his finger across the map. Simplified somewhat, France got rights to the area north of the line, Britain to the south.

Sykes had been an obvious choice to undertake the negotiations. Then a highly energetic Member of Parliament, he was known within the corridors of Whitehall as the ‘Mad Mullah’ where he had carved himself a job as an adviser on Middle Eastern policy to Britain’s leaders. Complicating his negotiation with Picot was the fact that the British had just made a vague promise to the Arabs of an empire after the war. Believing that the British would never have to honour any commitment to the Arabs, Sykes waved this earlier deal aside. He now privately admitted that his aim was ‘to get [the] Arabs to concede as much as possible to [the] French’. This was just as well, for Picot’s main negotiating tactic, according to another British observer, was ‘to give nothing and to claim everything’.

Sykes’s agreement came in for great criticism. Other British politicians and officials questioned the need to be so generous to the French, who had almost no forces in the region. Once the Americans had entered the war with their rhetoric of self-determination and President Wilson’s blistering attack on the “little groups of ambitious men who were accustomed to use their fellow men as pawns and tools”, the treaty – an old-fashioned imperial carve-up – looked increasingly anachronistic.

TE Lawrence’s discovery of the treaty's terms, in a meeting on the coast of Arabia with Sykes on 7 May 1917, spurred him to devise a strategy that was designed to wreck it. Lawrence believed that if the Arab tribesmen he was advising could cross the dividing line agreed by Sykes and Picot and reach the area of Syria promised to the French the treaty would be superseded by events, and worthless. And he succeeded: by the end of the war the Arabs had reached Damascus and Beirut, well inside the French zone.

As a consequence, and much against their instinct the French were forced to agree to a declaration that watered down the Sykes-Picot agreement. Sykes himself was by now worn out and deflated and under fire for an agreement which complicated the difficult situation in the Middle East. “Don’t take Mark at his own valuation”, whispered one colleague in London: “His shares are unsaleable here and he has been sent out (at his own request) to get him away.” Sykes had been sent to the Middle East to review the complex situation which he had helped to create. There he fell ill and it was probably this weakness that made him succumb to influenza at the peace conference.

In time Britain came to recognise the value of the Sykes-Picot agreement – if somewhat modified – to support its own developing imperial ambitions in the region. But local resentment of the treaty remains potent. ‘As I speak, our wounds have yet to heal … from the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 between France and Britain, which brought about the dissection of the Islamic world into fragments’, said Osama bin Laden in 2003, suggesting a modern parallel with “a new Sykes-Picot agreement, the Bush-Blair axis, which has the same banner and objective.”

Sykes’s unquenchable enthusiasm and sense of humour are shared by his family, who have authorised the exhumation. Government permission is still needed. Were Sykes posthumously to contribute to a cure for influenza it would be a dramatic and significant postscript to his controversial career.

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Might Sykes provide a flu cure?

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

The last chance

The National Library of Baghdad's brave chief, Saad Eskander, has been keeping a diary while the city falls apart around him. In the latest instalment he tells the agonising story of his frantic efforts to save the life of one of his librarians, who had been kidnapped.

Of the new security plan for Baghdad he writes that he told his brother how it "represented the last chance for us, and if it failed, it would be the end of the country and the escalation of the sectarian civil war on unprecedented level."

Jaw Jaw...

Reuters is reporting that British and American envoys will join representatives from Iran and Syria next month to discuss ways to stabilise Iraq. The approach - which was recommended by the Iraq Study Group but studiously ignored by President Bush - tends to confirm other reports that US efforts to quell the violence in Baghdad by means of a troop surge have not succeeded.

Earlier this week one of those who did the ground-work for the Northern Ireland peace agreement, Michael Ancram, pointed out the inconsistency between the American pressure on the British to open talks on Northern Ireland in the 1990s and their position now. Like all the best letters to newspapers, it is short, and well worth reading.

Corrupt poppy programme serves Taliban nicely

It looks as if the pre-harvest poppy eradication programme in southern Afghanistan is floundering.

This report suggests that the big players are escaping eradication by paying bribes. "The only people [whose crops are] being eradicated are those without money or connections," said one policeman quoted in the Daily Telegraph this morning. "On the eradication force, this is being called 'the season to make money'."

With a little over a month to go before the harvest, only about 5% of the 22,000 hectares targeted for destruction has been ploughed up: that's about 2% of the total area under cultivation this year. Expect a further rise in support for the Taliban as disillusioned farmers reject the corruption of the Afghan government and its employees.

Monday, February 26, 2007

Shootings in Saudi

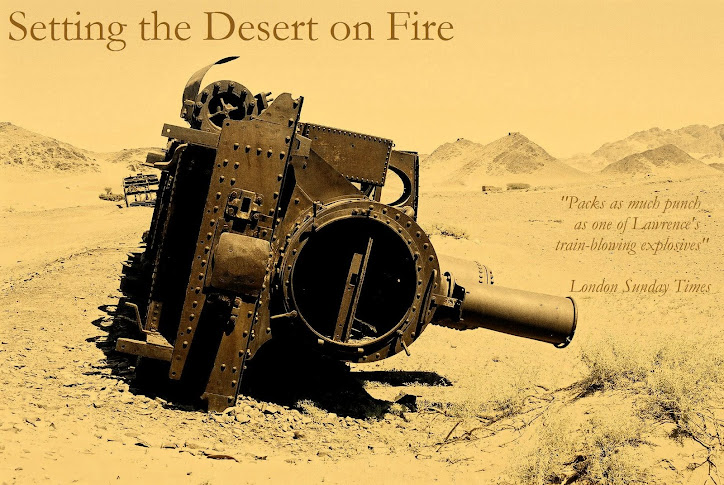

Madain Salih, Saudi Arabia

Madain Salih, Saudi ArabiaSunday, February 25, 2007

Will sending more troops to Afghanistan work?

Britain is sending up to 1,000 more men to Afghanistan, according to various reports this weekend. Sources have denied there is any link between the announcement last week that Britain would begin withdrawing troops from Iraq, but the move is uncannily similar to a plan leaked in September last year. In the newspapers, Robert Fisk argues that Britain has failed to learn from history, citing the destruction of the British army at the Battle of Maiwand in Afghanistan in 1880 as his evidence. But Christina Lamb takes the opposite view.

My view is that, while the British may yet fail in Afghanistan, their only chance of success lies in devoting much greater resources to trying to improve conditions in the country. The effectiveness of aid depends achieving greater security first.

Saturday, February 24, 2007

"A sign of our resolve"

The Daily Telegraph has several reports this morning that add up to a significant amount of sabre-rattling. Israel is apparently requesting permission from the Americans to fly over Iraq so that they can bomb Iran. Another report comes from an American aircraft carrier somewhere in the mouth of the Persian Gulf. This carrier, according to an American diplomat, Mike Gayle, speaking in London last night, is "a sign of our resolve". That was as direct a reply as he would give to the repeated question of whether the United States is willing to go to war with Iran.

The American doctrine of pre-emption has fewer supporters today than it did in 2002. That seems to be the reason why Mr Gayle was keen to suggest that, effectively, Iran is already at war with the United States, citing as evidence a dossier recently published by the US military. This showed photographs of weapons seized in Iraq which the Americans claim are Iranian-made and which they say proves that the Iranian government is behind a wave of devastating attacks on American forces using explosively formed penetrators. But there is a leap in logic there, as one US general has admitted: even if we accept the assumption that the weapons are Iranian-made, proving they have therefore been supplied by the Iranian government is a hard task given the fact that, as any expert on Iran immediately admits, the political structure in Iran is Byzantine in its complexity. And the Americans face considerably greater scepticism than they did five years ago.

The question of whether Iran is supplying weaponry to bog the Americans down in Iraq is misleading and designed to draw attention away from the central question of whether a pre-emptive attack on Iran to halt its nuclear weapons programme is either justified or likely to succeed, by suggesting the United States already has a casus belli for future action.

Friday, February 23, 2007

Advanced geometry

The ceiling of the mosque in the Amiriya Madrassah, Rada, Yemen

The ceiling of the mosque in the Amiriya Madrassah, Rada, YemenThursday, February 22, 2007

Was TE Lawrence a Zionist?

That's the claim the historian Sir Martin Gilbert makes in an interview in the Jerusalem Post today. He says that Lawrence had "a sort of contempt for the Arabs" and that he believed that it was "only with a Jewish presence and state would the Arabs ever make anything of themselves."

I wonder. Lawrence's strenuous efforts to champion the Arab cause hardly suggest contempt, and this should not be confused with the increasing exasperation he felt towards them by 1918, which was sparked by the unruly behaviour of the Bedu tribesmen. They were, he admitted at a low point, "the most ghastly material to build into a design."

Lawrence's interest in the Zionists arose from a meeting he had in Cairo in August 1917. There he met Aaron Aaronsohn, a farmer-turned-spy and Zionist who told Lawrence that his plan was for the Jews to buy up the land from Gaza to Haifa and ‘have practical autonomy therein’. On his travels in the region before the war Lawrence had thought that Jewish cultivation of the land would be a good thing. But now his reaction left Aaronsohn with the impression that he was ‘a Prussian anti-Semite talking English’.

By the summer of 1917, a Zionist Commission, headed by Chaim Weizmann, had been allowed to go to Egypt to pave the way for post-war Jewish immigration assuming the British invasion of Palestine was successful. In the background the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, believed that the Jews might be able to offer more assistance to the British than the Arabs. Appearing to help the Zionists would also camouflage Lloyd George's rather more imperialist ambitions in the region. But the British in Cairo had at that stage been given no instructions as to how to deal with the Zionist delegation, and this helps explain Lawrence's surprise and response when he heard the Zionists' plans at first hand.

A few weeks later Lawrence wrote to Sir Mark Sykes, the British politician who advised the Cabinet on the Middle East. In this letter (which Sykes never in fact received) Lawrence distinguished sharply between what he called "the Arab Jews" and the "colonist Jews (called Zionists sometimes)". The former spoke Arabic, the latter Yiddish. He asked Sykes: What have you promised the Zionists and what is their programme?’ Was the acquisition of land by the Jews, Lawrence asked, ‘to be by fair purchase or by forced sale and appropriation’? And, given that the Jews rarely employed Arabs on their farms, Lawrence wondered whether ‘the Jews propose the complete expulsion of the Arab peasantry, or their reduction to a day-labourer class’. He predicted trouble if in the future Arab states surrounded a Jewish state built on the lines Aaronsohn had laid out. He foresaw "a situation arising in which the Jewish influence in European finance might not be sufficient to deter the Arab peasants from refusing to quit - or worse!"

Lawrence's wartime ally Feisal initially took a rather more relaxed attitude towards the Zionists. At British instigation he met Weizmann north of Aqaba on 4 June 1918. Lawrence was not present at the meeting. There Feisal said that it was important that the Jews and Arabs cooperated, but he said that he was acting as his father’s agent and was unable to discuss the settlement of Palestine in detail, at least not until Arab affairs were ‘more consolidated’.

Feisal's attitude changed with time. At the Peace Conference in 1919, Lawrence presented a memorandum written by Feisal who was increasingly concerned about the Zionists, who were talking increasingly boldly about their hopes. The two men worked closely together, with Lawrence acting as adviser and interpreter. Of Feisal Lawrence once wrote "I usually like to make up my mind before he does". So it is likely that the memorandum also represented Lawrence's view. "If the views of the radical Zionists ... should prevail," it stated, "the result will be ferment, chronic unrest, and sooner or later civil war in Palestine." The memorandum made the same distinction that Lawrence had in his letter to Sykes: "with the Jews who have been seated for some generations in Palestine our relations are excellent. But the new arrivals exhibit very different qualities from those 'old settlers' as we call them, with whom we have been able to live and even co-operate on friendly terms. For want of a better word I must say that new colonists almost without exception have come in an imperialistic spirit. They say that ... under the new world order we must clear out; and if we are wise we should do so peaceably without making any resistance to what is the fiat of the civilised world."

The similarity of distinction between Lawrence's earlier letter and this memorandum seems to suggest that Lawrence took the view that Jewish immigration, which was the natural consequence of Zionism, would destabilise the region. Certainly he hoped for peaceful relations with the Jews who already lived in Palestine. He even believed that the Arabs would "support as far as they can, Jewish infiltration". But calling him a Zionist seems far-fetched.

Anyway, it will be interesting to see where Gilbert gets this idea from. His book, Churchill and the Jews, comes out in June.

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

Blair's withdrawal leaves Bush exposed

Though it has been broadly welcomed in Britain, Tony Blair's "announcement" today of a reduction in the number of British troops in Iraq is really nothing new. Goverment sources have been promising to withdraw troops for a while. One is left with the suspicion that the timing of the "news" has more to do with camouflaging the latest twist in the "cash for peerages" investigation going on in Britain, as well as preparing the ground for Mr Blair's approaching departure from Number 10. Another factor may be the opinion poll this week which showed that the opposition Conservatives, who broadly supported the war, have extended their lead over the government. Certainly there has been no sea-change on the ground in Iraq to justify the timing of the move. Despite official claims that Operation Sinbad - the effort to clear up sectarianism within the Basra police and military - has been a success, the violence, if anything is worse. And that is reflected in the fact that the withdrawal is actually happening much more slowly than one earlier report anticipated.

The announcement may have served the British Prime Minister nicely but, surprisingly, its timing has exposed President Bush, who has just ordered a surge of troops into Baghdad to try to stop the escalating violence. Bush's critics in the US are now using the clearly different directions of British and American policy to attack the President. The White House must be furious.

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Monday, February 19, 2007

DFID under fire in Afghanistan

A report in today's Daily Telegraph highlights the ineffectiveness of the aid "effort" in southern Afghanistan so far. Until recently Britain's Department for International Development (DFID) had no representatives at all in Helmand because it was too dangerous and criticism of the department's approach is mounting. The former provincial governor, Mohammed Daoud, is especially scathing. "Their QIP (Quick Impact Projects) I called SIP projects: Slow Impact Projects", the Telegraph quotes him saying. DFID's failure so far is, however, partly because there is no consensus about whether or not to destroy the poppy crop on which many of the local farmers depend, and mainly because there are not enough troops on the ground to create the security needed for aid projects - such as alternatives to opium production - to take root.

The starkest example of this is the fighting over the Kajaki dam, north of the provincial capital, Lashkar Gah. The dam should be able to provide much-needed electricity for the Helmand region, but the barrage needs an extra turbine and the contractors hired to fit it will not start work until the surrounding area is clear of Taliban. A small force of Royal Marines has been trying to drive off the insurgents. Their efforts have been well-reported. But they do not have the numbers to hold the ground they clear. Once they withdraw the Taliban reappear. Until more troops are made available, aid work in the region is doomed to fail.

Thursday, February 15, 2007

The best laid plans...

Saad Eskander's diary

Saad Eskander is the Director of Iraq's National Library and Archives. The British Library has been publishing his diary monthly. Here, rather belatedly, is January's instalment.

Tuesday, February 13, 2007

A Churchillian dilemma

With the Blair era drawing to a close, attention in Britain is now turning to the way in which his probable successor, Gordon Brown, might define a fresh start. One possibility is that he might order a rapid withdrawal from Iraq. The rumour is persistent because, while he has publicly supported the war, Brown has carefully also managed to sound rather sceptical about it. When asked whether he did support the policy before the last election on BBC Radio 4's Today programme, a millisecond's pause before his answer "...Yes", conveyed the opposite impression: "No."

Winston Churchill would have understood the dilemma well. In 1922 Britain was faced by a resurgent Turkey. Churchill, who had been lumbered with the job of dealing with Iraq, feared that the Turks would invade that country, then under the British mandate. Britain might have to send more troops to fight off an invasion, an outcome he knew would be extremely unpopular.

Churchill wrote to the beleaguered Prime Minister Lloyd George (to whom Blair increasingly bears an uncanny resemblance) on 1 September 1922: "I do not see what political strength there is to face a disaster of any kind and certainly I cannot believe that in any circumstances any large reinforcement would be sent from here or from India. There is scarcely a single newspaper – Tory, Liberal or Labour – which is not consistently hostile to our remaining in this country. The enormous reductions [in the number of troops stationed in Iraq] which have been effected have brought no goodwill, and any alternative Government that might be formed here ... would gain popularity by ordering instant evacuation. Moreover in my heart I do not see what we are getting out of it. Owing to difficulties with America, no progress has been made in developing the oil. Altogether I am getting to the end of my resources." (CHAR 17/27)

The same prospect haunts Mr Brown today.

Monday, February 12, 2007

The Kalashnikov index

Several references to the rising cost of an AK-47 in Iraq have caught my eye, as well as a mention of the so-called Kalashnikov index: the market rate for one of these weapons. However, no-one in the press seems to have put together the data to show the market trend, so I decided to do a little further research into the prices to produce the chart above.

It lacks sophistication: the bars show the range between the highest and lowest prices I could find quoted in any one year. There is enormous variation between the relatively peaceful Kurdish area in the north, and the Arab south, and significant differences between districts in the capital Baghdad. The genuine Russian-made weapon commands the highest prices; copies, either from Eastern Europe or the workshops on the lawless North-West Frontier in Pakistan are the cheapest. The price has varied from as little as $10 (when weapons were dumped on the market by the defeated Iraqi army) to $800 today.

The greatest variation can be seen in 2006, and this reflects the sharp climb in the value of an AK-47 which took place during the year. The attack on the al-Askari Shia shrine in Samarra in February last year is widely attributed to the sudden jump in the price of guns, as well as bullets, which nearly trebled in price to about 50 US cents apiece.

The Kalashnikov index is effectively a futures market for violence. Rising prices reflect rising expectations of violence in the future and attempts by the Iraqis to protect themselves. Succinct commentary on the market trend is provided by one dealer quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle. "This is not the time to sell guns, only to buy guns", he said.

Sources:

New York Times

Small Arms Survey

San Francisco Chronicle

Friday, February 09, 2007

Poppy update: cultivation up 70% on last year

This is the first report I've seen suggesting that this year's opium poppy crop in Afghanistan may dramatically exceed last year's record yield. I flagged up a report three months ago that the crop might match last year's. The explanation given by the head of Helmand province's agricultural department is refreshingly blunt. "Farmers are not receiving adequate support from the government", he admits, "so they are growing more poppy." He believes that there are 60,000 hectares under cultivation in Helmand, a 70% increase on last year.

This news arrives amid debate over what to do about the town of Musa Qala which, after Sangin, is the region's major opium market. The British withdrew from the town last year following a series of clashes with the Taliban, leaving the local elders to keep the peace. This negotiated solution attracted criticism from the Americans, criticism which has strengthened since the Taliban recently reoccupied the town. The Taliban commander, Mullah Ghafour, was killed shortly afterwards by a NATO airstrike, and some people are now arguing that a fuller offensive designed to drive the Taliban out of the town would also disrupt the harvest and the subsequent sale of the crop.

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

Meeting the Sadr family

With the influence of the Shia Sadr family firmly in the news in Iraq, some letters by Gertrude Bell have caught my eye. In a first she complains that

"It's a problem here how to get into touch with the Shiahs, not the tribal people in the country; we're on intimate terms with all of them; but the grimly devout citizens of the holy towns and more especially the leaders of religious opinion, the mujtahids, who can loose and bind with a word by authority which rests on an intimate acquaintance with accumulated knowledge entirely irrelevent to human affairs and worthless in any branch of human activity. There they sit in an atmosphere which reeks of antiquity and is so thick with the dust of ages that you can't see through it - nor can they."

And so, when an opportunity arose to meet the Sadrs, Bell accepted rapidly. She described them as "bitterly pan-Islamic, anti-British et tout le bataclan [the whole caboodle]".There follows an atmospheric description of her first meeting with the family, in the town of Al Kazimiyah, near Baghdad, in March 1920.

"The upshot was that I went yesterday ...We walked through the narrow crooked streets of Kadhimain [Al Kazimiyah] and stopped before a small dark archway. He led the way along 50 yards of pitch-dark vaulted passage - what was over our heads I can't think - which landed us in the courtyard of the saiyid's house. It was old, at least a hundred years old, with beautiful old lattice work of wood closing the diwan on the upper floor. The rooms all opened onto the court - no windows onto the outer world - and the court was a pool of silence separated from the street by the 50 yards of mysterious masonry under which we had passed.

Saiyid Hasan's son, Saiyid Muhammad, stood on the balcony to welcome us, black robed, black bearded and on his head the huge dark blue turban of the Mujtahid class. Saiyid Hasan sat inside, an imposing, even a formidable figure, with a white beard reaching half way down his chest and a turban a size larger than Saiyid Muhammad's. I sat down beside him on the carpet and after formal greetings he began to talk in the rolling periods of the learned man, the book-language which you never hear on the lips of others. Mujtahids usually have plenty to say - talking is their job; it saves the visitor trouble. We talked of the Sadr family in all its branches, Persian, Syrian and Mesopotamian; and then of books and of the collections of Arabic books in Cairo, London, Paris and Rome - he had all the library catalogues, and then of the climate of Samarra which he explained to me was much better than that of Baghdad because Samarra lies in the third climatic zone of the geographers - I need not say that's pure tosh.

He talked with such vigour that his turban kept slipping foreward onto his eyebrows and he had to push it back impatiently onto the top of his head. And I said to myself "If only that great blue turban of yours would fall off and leave you sitting there with a bald head I should think you just like everyone else." But it didn't and I was acutely conscious of the fact that no woman before me had ever been invited to drink coffee with a mujtahid and listen to his discourse, and really anxious lest I shouldn't make a good impression." [14 March 1920]

Within a few months her perception of the family changed. An uprising erupted in Iraq that severely tested British control. As Bell afterwards admitted, the Sadrs had played a crucial role in the violence.

"The villain of the piece is Saiyid Muhammad Sadr, the son of old Saiyid Hasan Sadr ... a tall black bearded 'alim with a sinister expression. [When Bell first visited in March 1920] Saiyid Muhammad was little more than the son of Saiyid Hasan, but a month later he leapt into an evil prominence as the chief agitator in the distrubances. In those insane days he was treated like a divinity. Shi'ahs kissed the robe of men who had touched his hand. We tried to arrest him early in August and failed. He escaped from Baghdad and moved about the country like a flame of war, rousing the tribes. It was he who called up the Diyalah tribesmen and caused all those tragedies .... His next achievement was on the upper Tigris. In obedience to his preaching the tribes attacked Samarra but were beaten off. He then moved down to Karbala and was the soul of the insurgence on the middle Euphrates. Finally, when the game was up, he fled with other saiyids and tribal shaikhs across the desert to Mecca..." [20 July 1921]

Muhammad Sadr returned to Iraq after the British declared an amnesty as a prelude to parachuting (the Sunni) Feisal in as king. According to Bell, Muhammad Sadr "intended to be second to Faisal, if indeed Faisal were not second to him, but Faisal can't bear him and he finds himself relegated to a position of comparative obscurity, with us, whom he hates, and our friends, whom he hates equally occupying the front of the stage. He has still a certain amount of influence and it's a hand to hand conflict between us and him."

And so began the struggle which persists today.

Tuesday, February 06, 2007

Can democracy solve the growing crisis in the Middle East?

Many people - particularly in America and Israel - don't believe that Syrian overtures for talks are genuine. But amid many reports that huge numbers of Iraqi refugees are causing concerns in Syria and Jordan, President Bashar Assad of Syria's comments in an interview with ABC news are worth noting. It is clear he fears a domino effect, with violence between Sunni and Shia in Iraq overflowing to engulf the wider Middle East. Some signs of this are already showing in northern Yemen, where a renewal in the Shia insurgency there looks like it may not be coincidental.

Assad's other comment, that the American ideal of bringing democracy to Iraq has done precious little good - "What's the benefit of democracy if you're dead?" he asked rhetorically - chimes with a thoughtful piece by former British soldier Zeeshan Hashmi in The Times. Towards the end he suggests: "Stop using the notion of democracy to justify loss of human life; we need to ensure that we create a more stable and less bloody future for coming generations. This is the least we owe to those who have made sacrifices. Political systems and doctrine can not effectively be imported from one region to another facing a different range of problems."

Thursday, February 01, 2007

British Library 0, London Library 1

My hope of looking at some interesting 1920s correspondence in the British Library yesterday was foiled because its staff were on strike. "Librarians on strike", as you probably are thinking, sounds rather stronger than it was. No braziers, yells of "Scab", and only a handful of rather forlorn staff holding limp placards. But it was a right pain.

So I went instead to the London Library in St James's Square. There you pay £180 for a year's membership, but it is possible to borrow books, and you get access to the shelves themselves, where the books are ordered by subject. So although you might be after one particular book, it could be that it's the volumes either side that catch your eye. It is an amazing place, and the fee is worth every penny. And so far, I have never seen the staff go on strike.

It also made me think harder about a piece in the Daily Telegraph by Sam Leith on Monday. Leith commented on the possibility that a funding shortage at the British Library might force it to charge for entry, shorten its opening hours, or reduce its collection. On one point, I agree with Leith. Cutting the collection would be to undermine the library's essential purpose: to hold a copy of every book published in Britain, and more besides. And I'd rather not see the opening hours shortened: for people like me, who want to do research after a day in the office, the library shuts too early already. Which leaves charging. And that, on yesterday's experience, doesn't bother me too much.

The best bit about Leith's piece is his comment that the British Library's "on-site catering, like its wireless internet access" is "extortionately priced and only intermittently satisfactory..." Last time I visited the library I could have sworn that the catering is run by the famous cook, Prue Leith. Who is Sam's aunt.