One of the aims of British policy in Afghanistan was to achieve sufficient security to make alternative livelihoods to growing opium poppies attractive. In the statement made by the then Defence Secretary (in the days before the post became a part-time job) announcing the original British deployment, eradication of poppy was a high priority.

This report then, which says that farmers in Helmand province are cutting down established fruit trees to grow more poppy, is a useful indicator of whether security has improved.

Friday, November 23, 2007

Helmand: progress report

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Unspoilt by progress

Tyre

TyreTuesday, November 20, 2007

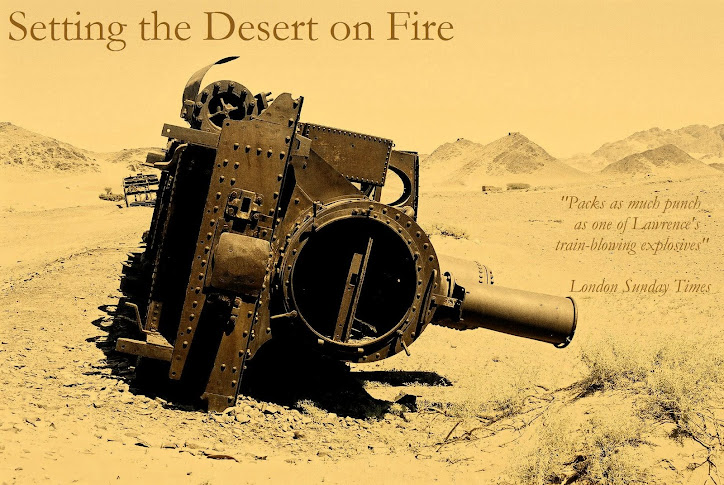

Archaeologists on the railway

Earlier in the summer I highlighted a report by the Great War Archaeology Group on their excavations of Turkish defensive positions along the Hijaz railway in southern Jordan.

They have just completed a second season of digging in the area. Alarmingly, their finds included several live hand grenades. This is their blog of their unique exploit.

Monday, November 19, 2007

Tension in Lebanon

One nearby country where the Index has surged is Lebanon. There, says this report, the cost of buying an AK-47 has recently trebled to $1,000 a weapon. Rising expectations of violence lie behind the rise. Lebanon's politicians are currently deadlocked over the choice of a successor to replace Emile Lahoud, the Syrian-backed president of the country. A replacement needs to be found by 23 November when Mr Lahoud's term ends, but as the Index suggests people are pessimistic that an acceptable compromise candidate will be found.

I got back from a short visit to Lebanon this morning, and my impression was that the country, though outwardly calm, is close to the abyss. Having given the Israeli army a bloody nose last year, Hezbollah is reputedly preparing for trouble. Its distinctive green on yellow flags (depicting a forearm clenching an AK-47) were flying everywhere that I went, south of the River Litani and up the Beqaa valley, where souvenir sellers offering Hezbollah t-shirts congregate outside the famous ruins at Baalbek. It is clear that the spectacular damage to the country's infrastructure done by Israel (and supported without demure by Britain and the United States) during last year's war, let alone the deaths the war caused, has only reinforced Hezbollah's support. And I watched a procession of cars of another pro-Syrian faction, streaming down the main road from the Syrian border towards Beirut, flapping their disconcerting, rather fascist-inspired, red, black and white banners from the windows. Despite the signs of wealth and renovation of Beirut's battered city-centre there seems to be a fatalism among the few Lebanese I spoke to about their ability to influence events, and even a certain ambivalence towards the current, if uneasy, peace. Perhaps this has always been the case. This was my first visit to Lebanon and I have nothing to compare it with.

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

The Balfour Declaration - ninety years on

The 90th anniversary of the controversial Balfour Declaration passed without much notice earlier this month. The Declaration was a mealy-mouthed expression of sympathy by the British government for Zionist aspirations. It was issued at this time because of a mistaken (and in itself decidedly anti-Semitic) belief that the Jews together wielded enormous hidden influence worldwide, and especially in Russia. There, British government officials forlornly hoped, the Jews might be able to halt the rise of the Bolsheviks. But the same day that The Times published the Declaration, 9 November, it also carried news of Lenin's successful coup in St Petersburg.

The Declaration also anticipated the capture of Jerusalem by British forces one month later. What had started as an aggressive defence of the Suez Canal had evolved into a military campaign. The pressing need for a victory of some sort to counterbalance bad news on the western front, and the perceived prestige of running such a sacred land were both reasons why it had.

But it was the cold logic of imperial strategy that was the fundamental reason behind the British invasion, and it was this that the Declaration sought to camouflage with its invocation of a moral cause for British actions, to a world that was increasingly cynical about imperial ambitions. As the significance of airpower began to be appreciated, it was Palestine's strategic value, as a buffer east of the Suez Canal and as a stepping stone between Europe and India that made it attractive to the British.

The development of aircraft that could fly ever further rendered Palestine ineffective as a buffer and irrelevant as an airstrip. Woolier hopes, that Britain could bring "a new order" in the Holy Land, "founded on the ideals of righteousness and justice" (© The Times's leader on the day after the capture of Jerusalem was announced) proved illusory for as long as the legitimacy of British rule was tied to the promotion of the Zionists' ambitions. Bruised by experience, public support for Zionism in Britain, which was probably never more than lukewarm, cooled quickly after 1948.

Some reasons why are put forward in a discussion here. Though I don't agree with all the analysis, the summary makes an interesting read.

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Remembrance Sunday

Friday, November 09, 2007

Australia

Monday, November 05, 2007

What would TE Lawrence had done in the Second World War, had he survived his motorbike crash?

Patrick - friend, fellow (and much more frequent) blogger and occasional thoughtful commenter to this effort - has come up with an interesting question. "What would have happened", he asks me, "had TEL not gone for a motorbike ride in Dorset? What role may he have played during the Second World War?"

Normally I try to avoid counterfactual history, because I have a prejudice that dwelling on the what-might-have-beens is the preserve of fiction (and I have a feeling that a novel based on just this premise has been written at some stage; I've never read it). But I'm going to make an exception. I'm going to invite you into the dark and faintly mildewy tent of Mystic Barr, relieve you of a fiver, gaze into my crystal ball and ponder the question: what if Lawrence had been alive in 1939?

It seems likely that Lawrence would by then, or would soon, have been asked to help. In his resignation letter from the civil service in 1922, he wrote: "I need hardly say that I'm always at his [Churchill's] disposal if ever there is a crisis, or any job, small or big, for which he can convince me that I am necessary." Churchill replied, gratefully: "I feel I can count upon you at any time when a need may arise."

Churchill himself wondered what Lawrence might have done. "I had hoped to see him quit his retirement" he told reporters on the day that Lawrence died, "and take a commanding part in facing the dangers which now threaten the country". He added: "In Lawrence we have lost one of the greatest beings of our time."

Three broad options might have been open to Lawrence. A role within the military, within the Foreign Office, or at home within, or working for, the British government, especially after Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940.

By 1940 Lawrence was fifty-one years old- a tough and active man, for sure, but well above the upper age for volunteering for active service. The compelling possibility that Lawrence might have played an active military role during the Second World War, though attractive, therefore seems unlikely. But who knows? Lawrence was adept at bending rules. And others served in frontline roles: Lawrence's sometime opponent, the MP and former proconsul in Iraq, Sir Arnold Wilson, died serving as a tail-gunner in an aircraft covering the Dunkirk evacuation. And he was fifty five.

Might therefore have Lawrence returned to serve in the Middle East - perhaps in North Africa? This is where the counterfactual throws up some interesting points. Part of the reason for Lawrence's fame by 1939 was precisely because he was already dead. His death four years earlier cleared the way for the general publication of his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, of which, up to then, he had only had about 200 copies printed. He did give one of them to Archibald Wavell, who would command British forces in the Middle East early in the war and who encouraged the development of the famous Long Range Desert Group. But Wavell remained a controversial figure (Churchill eventually replaced him) and I wonder whether he would have been able to stand behind the LRDG had the trade edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom not already become a huge bestseller. The book certainly enthused some of his men. As one of the leaders of the Long Range Desert Group wrote in his own memoir: "Lawrence had lit the flame which fans the passion of those who lead guerrilla warfare and I wanted more than anything to experience it." So there remains a question as to whether, had Lawrence lived and Seven Pillars of Wisdom remained unpublished, he would have had as great an influence as he did because he was dead.

There were other jobs on offer in the Middle East. To coordinate the military and political efforts in the region, Britain posted a minister of state to Cairo. However, this role involved liaison with the Free French after Syria and Lebanon were taken back from the Vichy regime in 1941. To them however, Lawrence was anathema and it is highly unlikely that he would have been an acceptable candidate, particularly because the Foreign Office was anxious throughout the war to reduce friction with the French as far as possible. There were other diplomatic jobs. In early 1941, when it became clear that the government in Iraq was being subverted by Axis propaganda, the British government sent Lawrence's wartime colleague Kinahan Cornwallis to Baghdad to serve as ambassador. While he was there, Cornwallis effectively coordinated the military operation which ousted Rashid Ali al Gailani, who seized power in a coup in April that year. Given Lawrence's own interest in Iraq, and his knowledge of the region, this is certainly a role that would have been open to him. But - the problem with imagining Lawrence in any governmental job is that he had upset many civil servants during his earlier service and these enmities would inevitably have worked against him had Churchill dropped him into any job. A comparable figure was Sir Louis Spears, an MP whom Churchill made his special envoy in the Levant from 1941. Spears found himself under attack from almost every direction. Again, it is highly unlikely Lawrence could have fulfilled this role because of his known dislike of the French. Perhaps he might simply have served as an adviser, in Whitehall, to Churchill. Churchill numbered Lawrence, after all, was one of "the two or three of the very best men it has ever been my fortune to work with."

At home other opportunities might have been open to him. In his final years in the Royal Air Force he had worked on developing rescue boats that were to play a vital role during the Battle of Britain picking up airmen who had ditched into the English Channel. It is possible that he might have played a greater role in this capacity during the battle for British airspace in 1940-41. But given Churchill's like of Lawrence - and his appreciation of Lawrence's fame - it is hard to believe that he would have left Lawrence working on such an important, but fundamentally unglamorous project. Could Lawrence have worked at home for the Special Operations Executive, taking on a Maurice Buckmaster-type role? I don't know enough about the Political Warfare Executive to do more than raise that question. But with that thought, one last possibility comes to mind. Might Churchill have theatrically appointed Lawrence the guerrilla leader to lead the preparations to fight the Germans on the beaches and the landing grounds had Hitler invaded in 1940? Perhaps it is here, among the Home Guard - many of them old soldiers of the First World War - that Lawrence would have found his niche. It is, of course, impossible to know for sure.

Thursday, November 01, 2007

British "diplomats" bite back

On Monday we learned that, according to the Americans, the Taliban were taking MI6 for a ride.

Then on Wednesday we heard that, according to British "diplomats", a key tribal leader in Helmand was on the verge of defecting.

Could these two articles possibly be related?

Uxbridge here I come

I'm speaking next Wednesday, 7 November, at Uxbridge Central Library. T. E. Lawrence spent ten weeks in Uxbridge in 1922, under the guise of "Aircraftsman Ross". He had joined the Royal Air Force after handing in his resignation to the Colonial Office where he had served as Winston Churchill's adviser. By odd coincidence on 7 November it will be exactly 85 years to the day that Lawrence finished his basic training at the Uxbridge depot. My job next week will be to explain why he ended up there.

Lawrence had been spared the rigours of basic military training when he volunteered in 1914 and throughout the war he maintained an amateurishness (in the approving, British sense of the word) that often infuriated other professional soldiers. His experience at Uxbridge changed him profoundly. "The person has died", he wrote, "that to the company might be born a soul." Three years later he would write that "Uniform is like corsets …. you get used to the support of it, and feel undone if it is taken off you in the end of time."