Friday, February 26, 2010

Saturday, January 23, 2010

In the sticks

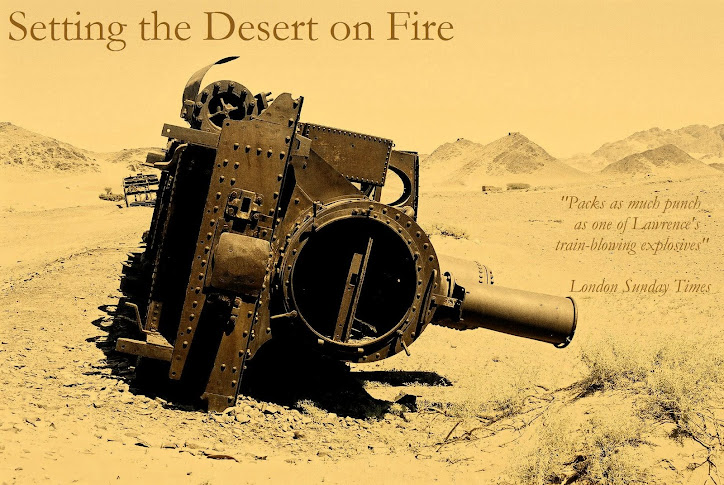

Trying to write up the day's events before it gets too dark to see - in the desert west of Mudawarra, southern Jordan, 2004

Trying to write up the day's events before it gets too dark to see - in the desert west of Mudawarra, southern Jordan, 2004Fortunately, I don't spend all my time hunting for information in the archives. It was a visit to Syria in 2002 to see the crusader castles that sparked my interest in T.E. Lawrence - and to complete the research for my book about the Arab Revolt, Setting the Desert on Fire, I then went to Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, going deep into the desert to see the places in the story for myself.

The photograph above was taken at the end of the first day of a two day trip to Mudawarra, which ninety years ago was a key railway station on the Hijaz Railway that Lawrence was anxious to destroy. Now close to the Jordan/Saudi border, the station lies in an area with abundant water supplies, and Lawrence believed that, if he could knock it out, the railway would become unusable, as the locomotives depended on water for steam.

Mudawarra lies on the Mecca road southeast of Maan, but by far the more interesting way to get there is just as Lawrence did, directly cross-country from Wadi Rum. Before I started writing the book I was keen to get more of an idea of the forty mile journey the raiders had to make to the railway, and the conditions they faced, so I organised a guide in Wadi Rum - Attayak Ali - and headed with him in a four wheel drive east out of the Wadi, and into the desert. Very quickly it feels very far from anywhere.

With a generous stop for lunch, it took about half a day to drive there, bumping across the stony, Jordanian desert, leaving a wake of yellowy-grey dust behind us. The picture above shows why, following the capture of Aqaba in July 1917, the British shipped in armoured cars and tenders to mount operations against the railway: this is (mostly) ideal country for motorised hit-and-run attacks.

We reached Mudawarra by mid-afternoon. Much of the railway station - including its all-important water tanks - was finally demolished by the British in August 1918 and what remains is now occupied by the police, who offered us a cup of tea. Then we then turned back, southwest-wards, into the desert, to find a place to spend the night.

Writing up the diary at the end of a long and hot day is invariably a chore, but it is well worth it in the long run. I find the diary reminds me far better of what the day was like than pictures I took, like the one above. It was the first time I had ventured into the desert and I was surprised by how much I had seen that day:

"The desert is not deserted. There are Bedu in their brown tents - hard to spot, and closer to the water sources in this dry season of the year [it was September]; camels loping across the desert; flies which swarm as soon as we stop; tracks of more camels, foxes, rabbits, snakes. Sand-coloured birds."

To see the debris of this forgotten battlefield you have to go much further south, however. That was why, the following year, I also went to Saudi Arabia.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

In the archives at the Chateau

Archives specialise in petty rules. You may need a document to corroborate your identity on arrival; to have booked an appointment in advance; have a letter of reference from a publisher. I have seen a grown man (he was a Turkish civil servant) reduced to the verge of tears by the access policy of one establishment. He had come all the way from Ankara and was on a tight deadline. He had no idea that the archive he had come to visit was only open for just over five hours a day, because of budgetary constraints.

All this means that I am always nervous when I arrive at an unfamiliar place, and all the more so if any conversation I have to have is in a foreign language.

The atmosphere upstairs at the chateau is a good deal more welcoming than the chilly entry hall. Although the temperature outside is sub-zero, large, tall windows, golden wooden panelling and generous use of central heating make my first stop in the archive a pleasant place to linger. However, I have to avoid this temptation. The first task is to locate the documents I want to look at, and get some ordered as fast as possible. The documents will take at least half an hour to be brought out of the archive for me, and there is already less than eight hours to go today. Time, therefore, is of the essence.

Archive catalogues in Britain are increasingly electronic, making the researcher's task quicker, since likely documents can be identified, ordered, and even viewed from home. The French are somewhat behind the curve however, and so my first task was to look through the paper catalogues filed in the search room. Fortunately there is some help online, making the job quicker on arrival. On this visit, I was particularly interested in records relating to the First World War, the 1925-28 period, and the Second World War. Picking a few to start with has a close resemblance to a lucky dip, but I was quickly on my way. Once into the reading room, I was able to give my list to the invigilator at the desk who types the numbers into the system. Then there is a wait.

My spoken and written French are perfectly good but slow, so a newish policy operated by the archive is going to be a major help. They will allow you to take photographs for personal use. So as well as a laptop, and a notebook and pencil (no pens, of course), I have brought my camera. Other researchers have gone further, bringing tripods to make the process of taking hundreds of photos as painless as possible. After a day spent looking over a desk holding up a heavy camera, I can see why they do. All I need is a seat nearish to a window.

My name is shouted by a French soldier in the corner of the room who is in charge of handing the boxes out to visitors, and I go to fetch a large, cold 'carton' of papers which has clearly come from somewhere that is not heated. They are frequently in a dreadful state. Wartime rationing means paper of poor quality, and many of these files have been kept for years in humid, hot conditions. Some of them are drilled by woodworm. The pins and tags that hold others together, have rusted through, and disintegrate in one's hands. I like these signs of age and neglect, however, because they imply that few people have bothered to look through them. A new paperclip, or the restorer's laminate on a fragile piece of paper suggests that others may already have been looking through them recently.

The job that follows is, I imagine, similar to a spy's. I need to skim the contents of these boxes, often containing several hundred sheets of fine paper, as rapidly as possible, assessing which look interesting, and photographing each of these. I have twenty four hours in all to do so. I take all the photos in black and white, since this means I can fit more on a memory card. Periodically, I download batches of two hundred or so photographs onto my computer.

The time limits on these trips requires an intense schedule. I tend to have as big a breakfast as possible, so that I do not need to stop for lunch. The day will normally bring up a handful of fascinating items, and to keep my interest up, I will sometimes stop to read a little. At Vincennes, one document that catches my eye is the record of an interrogation of a Druze leader who was wounded and captured in 1926, and makes some fascinating allegations about the British. Another is a reference to a man I have been hunting for several months, but interestingly, refers to his role as an intelligence officer in a controversial counter-insurgency operation outside Damascus years before. There will be a great deal more to say about this latter gentleman in the book.

Monday, January 18, 2010

Rory Stewart's Legacy of Lawrence of Arabia

I had a walk-on part in Rory Stewart's two part documentary on T.E. Lawrence's legacy, which was broadcast on BBC2 on Saturday, and can be downloaded on Iplayer. The film is well worth watching, and Stewart does a very good job of linking Lawrence's pre-war travels as a student, then an archaeologist, then effectively a spy, with his wartime role. There's some superb footage of the southern Jordanian desert from the Batn al Ghul escarpment and overlooking the Gueira plain, just north of Aqaba.

I had a walk-on part in Rory Stewart's two part documentary on T.E. Lawrence's legacy, which was broadcast on BBC2 on Saturday, and can be downloaded on Iplayer. The film is well worth watching, and Stewart does a very good job of linking Lawrence's pre-war travels as a student, then an archaeologist, then effectively a spy, with his wartime role. There's some superb footage of the southern Jordanian desert from the Batn al Ghul escarpment and overlooking the Gueira plain, just north of Aqaba.

Incidentally, the phrase that I used in my interview to describe the line that Sykes proposed, "from the E in Acre to the last K in Kirkuk" is Sykes's and not mine. These were the precise words that Sykes used when he explained his scheme for the partition of the Middle East with France, and they speak volumes about the manner of the British approach. Here is the extract from the minutes:

Friday, January 15, 2010

In the archives

This year's snow reminded me of last year's - and how it nearly wrecked a research trip I had planned.

Original research forms the heart of my approach. I've spent the last two years in various archives gathering the information that I will use to write my current book. This is slow work. On some days I find nuggets, on others, none. There is always the temptation to cut corners. If I based my books on others' work, I could write more, and faster. As a consequence I might be better-known and richer. But I would always feel that I was an interpreter, rather than an explorer. I would not have the same feeling that I am bringing the reader something that is genuinely new. And the only way to do that is by going into the archives.

This new book, which covers the era between 1915 and 1948 when Britain and France divided and then ruled the Middle East between them, required several weeks' work in France. There were two places I had to visit: the Centre des Archives Diplomatiques, in the suburbs of the western city of Nantes, and the imposing Chateau de Vincennes, in east Paris. This time last year I was in Paris.

The Chateau is, as the name suggests, the best defended archive that I have ever visited. No other set of papers I have looked at is protected by a drawbridge. It is the home of the Service Historique de l'Armee de Terre - housing the French army's historical records. Like all things French, there is a certain amount of bureaucracy involved in getting in to look at them. You have to register with the archive when you first visit. You cannot order documents before your visit unless you have a registration card.

Last January I had booked my tickets to go to the Chateau in Paris. Then came the snow and on the day before I was due to take the train to Paris, on the website a notice appeared, warning visitors not to come unless they had already ordered documents. I had not ordered documents, because I was not registered. The choice was between writing off the Eurostar tickets, or pressing on regardless and hoping that the rules were flexible. I took the latter option.

Early on 7 January, I crossed the drawbridge and walked to the reception centre where I would apply for my ticket. I was apprehensive: this could turn out to be an expensive waste of time. My spoken French is also pretty slow. So I had rehearsed a few sentences explaining my predicament.

"Je suis historien anglais" turns out to be a very useful phrase.

The woman in charge of visitor registration initially caused my heart to sink. Had I not seen that the Chateau was shut today, because of the bad weather? I lied, saying I had not. I had come all the way from London and this was my first visit. Hence my predicament.

The atmosphere improved. Forms were produced for me to fill. A registration card was printed. My shoulders dropped at least an inch, and I left the hot office, crunching across the snow towards a forbidding looking Napoleonic barrack-block where, I was told, the archive was based.

Friday, January 08, 2010

'Faces' from the Yemen No. 5

When I was in Yemen, three years ago, I commented on the colourful traditional dress that many Yemeni women wear, and got an interesting reaction. Traditional dress was dying out, a Yemeni man told me. Instead, he said, more and more women were wearing black abayas - influenced by Saudi habits to the north.

It struck me then, and much more now, that there is an important metaphor here. As local and international politicians seek to blame Yemen for the problems that are festering there, it would be useful to ask the question of where the influence that drives them comes from. The answer, as with fashion, is, from the fundamentalist state that lies directly north.

Thursday, January 07, 2010

Faces from the Yemen No. 4

"The poorest nation in the Arab world struggles with 27% inflation, 40% unemployment and 46% child malnutrition. Half of its 22 million citizens are under sixteen and the population is set to double by 2035."

Wednesday, January 06, 2010

Faces from the Yemen No. 3

After I took this man's photograph, he took one of me, using the camera on his mobile phone.