If the British government loses a parliamentary motion tonight it will be obliged to call a public enquiry into the conduct of the Iraq war. Faced with this unappealling prospect, it has resorted to a hysterical attack to try to stop the rot, denouncing its Conservative opponents - who can probably tip the balance - as traitors. The Sun reports the Tony Blair's spokesman as saying: 'We have an enemy looking for any sign of weakness at all, any sign of a loss of resolution or determination to see this job through.'

Any mujahideen with access to the internet - and the signs are there are plenty of them - would see from a cursory reading of the British press that there are plenty of 'signs of weakness' already. Every recent opinion poll in the British papers shows that public support to 'see this job through' is rapidly waning. The pro-war papers themselves have been trimming to chime with their readers' more sceptical views. And when the head of the Army says that the British army should 'get ourselves out sometime soon because our presence exacerbates the security problems' caused by intervention and Mr Blair says he agrees, then the government's attack today looks ridiculous.

The underlying problem is that the Government has relied all the way on Conservative support for its Iraq policy. Its claims on weapons of mass destruction - which turned out to be nonsense - enjoyed an easy ride in Parliament because of the Conservatives' readiness to believe them. During the war that followed, the Conservatives have been more gung-ho than the government. Had they been more circumspect in their support from the outset, they would be way ahead in the polls by now.

That is changing. For the Conservatives, the appetising prospect of winning votes finally seems to have outweighed the trenchant support for the war they have espoused until now. That is why the government is so worried tonight.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

More gung-ho than the government

Monday, October 30, 2006

The first cuckoo of spring?

Lots of interesting information in the media over the weekend on the situation in Afghanistan. The Independent on Sunday reports that British soldiers have now stopped patrolling in the regional capital Lashkar Gah because the threat from suicide bombers is too great. A marine was killed in a similar bombing in the town ten days ago. It also suggests that the incoming Royal Marines Commando force, which has taken over from the Parachute Regiment, does not share the Paras' view that the Taliban have been tactically beaten. And the Royal Marines' view is that the aggressive defence forced on the Paras has been counter-productive. 'For every Taliban you kill', the 42 Commando spokesman is quoted saying, 'you recruit three or four more' . The view has not filtered down to the soldiers now confined to Camp Bastion, the British forces' base in the province. 'What we really want to be doing is fighting' one bored soldier tells the Mail on Sunday.

There has been less fighting recently in northern Helmand - possibly because of Ramadan or the poppy-planting season - but British troops guarding the hydro-electric dam across the river Helmand at Kajaki continue to be attacked. A Guardian article last week suggested that it was a botched special forces operation which precipitated the violence seen earlier this summer.

A fascinating question and answer session with David Loyn, who reported on the Taliban, last week (the report was the target of some kneejerk criticism) sheds more light on the complexity of the situation and helps explain why the Taliban enjoy the support they do.

Finally, Lord Guthrie, the former Chief of Defence Staff, is interviewed in the Observer. He reveals his scepticism of the chances of success in Afghanistan with the current levels of men deployed and, more damagingly, rightly questions whether Tony Blair's offer of 'whatever equipment' is needed can be delivered. And he makes a none too subtle swipe at John Reid, the former Defence Secretary who ill-advisedly expressed his hope that British troops would leave Afghanistan without firing a shot. 'Anyone who thought this was going to be a picnic in Afghanistan - anyone who had read any history, anyone who knew the Afghans, or had seen the terrain, anyone who had thought about the Taliban resurgence, anyone who understood what was going on across the border in Baluchistan and Waziristan [should have known] - to launch the British army in with the numbers there are, while we're still going on in Iraq is cuckoo.'

Friday, October 27, 2006

Oxford seminar

The seminar kicks off at 5.15pm, at the Middle East Centre, 68 Woodstock Road, Oxford.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Insight or propaganda?

Last night's Newsnight piece on the Taliban in Helmand, Afghanistan, was a piece of superb and brave journalism by the war correspondent David Loyn. Loyn risked his life - or at least put a huge degree of trust in the Pashtun honour code - to go behind the lines in Helmand and investigate what is going on. Last month the outgoing British commander Brigadier Ed Butler said that the Taliban had been tactically defeated. Loyn's report suggested otherwise. The Taliban are free-range, well armed (with captured night vision goggles and .50 cal machine guns among other things) and enjoy some support from local people who are aggravated by corruption, which commonly takes the form of illegal roadblocks charging 'tolls'.

Today, various Conservative politicians in Britain are getting hot under the collar about the report. Julian Lewis said it was 'unalloyed Taliban propaganda', while Liam Fox described it as 'obscene'. But the Tories should stop trying to do the government's job for it, and start shouting louder for the reinforcements the British need to send to Afghanistan, if they are to have a hope to achieving what they want to. What the report so clearly showed was that the government is wrong to claim that it is winning in Helmand, and as the opposition the Conservatives should be asking why that is.

What the report did not go into was the Taliban's claim to have outlawed opium production when they were in power. Up to a point Lord Copper. The Taliban earned duty from exports of the drug and did not want over-supply to the value of the commodity and so the income they derived from it. Money, not religion was the motive for the ban, and it would have been good to hear that aired.

Monday, October 23, 2006

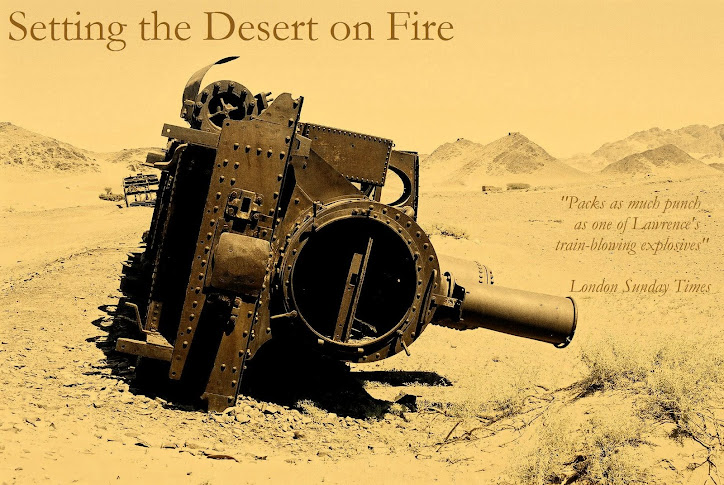

The Hijaz and Helmand

Exactly ninety years ago this month, a short, fair-haired young man with piercing blue eyes stepped off a launch onto the quayside at Jeddah on the eastern shore of the Red Sea. The port stood at the edge of the Hijaz, the formidable chain of serrated ochre mountains that hid Mecca and Medina, the holiest cities in the Muslim world. ‘The heat of Arabia’ he would later write, ‘came out like a drawn sword and struck us speechless.’ Arabia would make him famous, for his name was TE Lawrence.

Lawrence had arrived in Arabia to rescue a tribal uprising, backed by Britain, that had expelled the Turks from Mecca but which had now run out of steam. The Turks looked set to retake the holy city and seemingly, the easiest way to stop that happening would have been to send the tribesmen British reinforcements. But British troops were scarce, and deploying them to such a sensitive area was deemed unwise. Lawrence was forced, through desperation, to consider other tactics. ‘The Hijaz war is one of dervishes against regular troops’, he quickly realised, ‘and we are on the side of the dervishes.’ This was revolutionary and provocative. One senior officer, a veteran professional soldier who with Kitchener in the Sudan had defeated the dervishes, called Lawrence ‘a bumptious young ass’ who ‘needed kicking, and kicking hard at that.’

But Lawrence had a point. A classic military manual of the era, Small Wars, contained a timeless warning for its readers: ‘Guerrilla warfare is what the regular armies always have to dread, and when this is directed by a leader with a genius for war, an effective campaign becomes well-nigh impossible.’

Lawrence was to prove this maxim right again. He advocated sending a handful of British advisers to direct the Bedu, armed with copious quantities of gold and dynamite. ‘This show is splendid’ he wrote a short time later to a colleague who was about to join him. ‘You cannot imagine greater fun for us, greater fury and vexation for the Turks’. It was frustrating, because as Lawrence commented after the war, ‘Many Turks on our front had no chance all the war to fire on us’.

Over the next two years Lawrence honed his unorthodox strategy, with results can still be seen today. Blown-up locomotives, half-sunk in the desert sand. Lonely stations pock-marked with bullet holes. Graves with jagged shards of rock for headstones. A handful of daring British officers and their Bedu helpers pinned down 11,000 Turkish soldiers,who never did re-enter Mecca. The Hijaz Railway never worked again and today its track has vanished altogether.

When Lawrence looked back on his own exploits afterwards, he believed that the Turks would have needed 600,000 men in all, at least twenty soldiers in fortified posts every four square miles, to have defeated the insurgency. That was the tactic that had beaten the Boers in southern Africa and the Mohmand tribesmen on the North-West Frontier. The British were not squeamish about how they subdued the Mohmands, great-grandfathers of the Taliban. The blockhouses they built at eight hundred yard intervals were linked by electric fences that, the local governor reported, had killed ‘two Mohmands, six dogs, seven jackals and one cat’.

Seven hundred miles to the south-west today, across the border in Afghanistan, British troops are again trying to deal with an insurgency. The heat and the landscape of Helmand province, southern Afghanistan, have strong similarities with the Hijaz, and the tactics the Taliban are now employing are eerily familiar. ‘They didn’t come out and fight anymore’, one young soldier said: ‘I didn’t have to fire a shot’. Yet in this dusty region, which is a quarter the size of the Hijaz, Britain has deployed barely 5,000 men in isolated pockets: nowhere near enough to achieve the security they were tasked with achieving, sent by a government that, like the Turks in Arabia ninety years ago, refuses to admit defeat.

As Lawrence proved, too few troops, defending too large an area is a vulnerable combination. The British army knows it. It has now started to withdraw troops from the isolated outposts it occupied around the province earlier this summer under pressure from the energetic local governor, Mohammed Daoud. Daoud’s strategy is the right one – there can be no significant reconstruction without a great improvement of security across the province – but the British government has not supplied the resources to sustain it. As a consequence, British soldiers have been too thinly spread and, just as the Turkish railway was an easy target for Lawrence, their own lifeline to the outside world – by helicopter – is very exposed to Taliban attack.

Britain’s prime minister, Tony Blair, has offered the troops in Helmand ‘whatever’ equipment they need. But by Lawrence’s calculation, it is thousands more men that are required, up and down the towns and villages of the Helmand river, to make conditions safe enough for aid work. Without those reinforcements, the reconstruction effort – designed to wean the local economy off opium production which, it is believed, helps fund Islamist terrorism – is doomed to fail. The situation is too dangerous for aid workers at the moment, and so far, just two bazaars have been rebuilt. Meanwhile an estimated 70,000 children cannot get an education because Taliban intimidation has closed their schools.

Security provides the foundation for reconstruction and reconstruction is crucial for winning the battle for hearts and minds which will defeat the Taliban. Here the forceful British tactics seen so far are not succeeding. ‘The British brought nothing but fighting’, complained the turbaned elders of one town. ‘Women have been killed. Children have been killed’, mourned one man in another. As Lawrence noted, his own success depended on ‘a friendly population, of which some two in the hundred were active, and the rest quietly sympathetic to the point of not betraying the movements of the minority.’ Much is made of Lawrence’s leadership. But the truth is that the alliances he formed were bought with gold.

Ninety years on, Lawrence’s advice is simple and still relevant. Many more men and much more money are both needed if the British are to have a hope of winning in Helmand.

Friday, October 20, 2006

Food fight

As my good friend and blogger Tom observes, the Middle East has a new front.

Outside his supermarket he found campaigners urging him to Boycott Israel. In my local supermarket, that would be difficult. The only thing I can think of that comes from Israel, is rosemary: something which, incidentally, grows perfectly well in Britain. But it's a growing trend. A Palestinian olive oil producer makes great play of its political credentials. The Israelis, meanwhile, are fighting back. But a lot of the links don't seem to work. Who will win the food fight?

Friday, October 13, 2006

A crime to deny the Armenian genocide?

The French Parliament voted yesterday to make it a crime to deny the Armenian genocide committed by the Turks between 1915-17. The killings happened during the First World War and while the Turkish government continues, rather half-heartedly, to pretend they never happened, or at least were not a genocide, the evidence is compelling. At first sight the Parliament's vote might seem a good idea. The French Armenian community welcomed it, after all.

The French Socialists who backed the vote, have interests closer to home, and much less noble. They are trying to win anti-Turkish feeling, which is already strong in France. The French, who consider themselves the architects of the European Union, generally do not support Turkey's hope of joining the club they feel they founded. And yet to exclude Turkey would only reinforce the divide between East and West, already so visible elsewhere. The socialists of course, also fear cheap Turkish labour taking jobs in France. where unemployment is obstinately high. This low motive, not high morality, lies behind the law.

Turkey's ongoing refusal to admit the killings were systematic is ridiculous, agreed. But far better to do what else happened yesterday and award the leading Turkish novelist and historian, Orhan Pamuk, the Nobel Prize for Literature. Pamuk has already publicly talked about the genocide, which is a crime in Turkey. But he is too famous to be imprisoned, and other novelists put on trial for doing the same have also been acquitted. This approach of praising the freedom of speech, and not a law which does the opposite, is the way to safeguard the truth.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

I've just watched a quite astonishing interview on the BBC's news analysis programme Newsnight, following on from the leaked document I covered earlier. In it, Sir John Kiszely, the director of the Defence Academy, a Ministry of Defence think-tank, tried to claim that what Newsnight had revealed was the "raw material" not a finished, polished view. Newsnight effectively rubbished that, but what was most interesting, was when Kiszely tried to fend off a question on whether the document was an accurate reflection of the current state of play in Iraq and Afghanistan, with the wonderful answer: “This is not an area of my expertise”. Sir John has served as the Senior British Military Representative in Iraq.

There's something odd about all this. Why, if Newsnight was so wrong, did it take the Defence Academy 12 days to rebut its allegations? And, if not in the two main areas of active British deployment, one of which he has served in, what is Sir John an expert in, then?

Thursday, October 05, 2006

The view from Helmand province, Afghanistan

There are some contradictory reports coming from Helmand province in Afghanistan, where British troops are deployed on a mission which was originally billed as a reconstruction effort designed to wean the local economy off the opium trade. Since then it has become clear that British troops are fighting a war so dangerous that it has largely gone unreported, except by the soldiers themselves.

The question is how that war is going.

Let's start with the view of Brigadier Ed Butler, the commander of the UK Task Force and 16 Air Assault Brigade, the unit which is about to finish its tour in the province. Reviewing the previous six months - which he described as a "war of attrition" - on 27 September he said: "I think we've won, we may not be quite there yet this year". He was referring to the tactical battle to defeat the Taliban. Butler also reported that "a secret deal" had "brought a halt to violence" in Musa Qala, a government outpost in northern Helmand.

Further revealing details about that secret deal have since emerged. "We were not going to be beaten by the Taliban in Musa Qala," the Daily Telegraph quoted Butler as saying, "but the threat to helicopters from very professional Taliban fighters and particularly mortar crews was becoming unacceptable. We couldn't guarantee that we weren't going to lose helicopters." Let alone the logistical problems losing a helicopter would cause (the British have only 6 Chinooks available at the moment), knowing that such a loss would cause significant political fallout in Britain, 16 Bde were compelled to conclude a deal, brokered by Afghan elders: the British won't shoot if the Taliban don't shoot at them. The elders are expected to persuade the Taliban not to attack - precisely the task of British troops, who were supposed to be protecting the reconstruction effort. The real reasons for the truce are 1) British forces are overstretched and underequipped and 2) having sold the mission to the public as a reconstruction effort British politicians do not believe that the public will tolerate casualties.

There is now a lull in the fighting, according to the British. "I fully acknowledge that we could be being duped; that the Taliban may be buying time to reconstitute and regenerate," Butler told the Daily Telegraph. "But every day that there is no fighting the power moves to the hands of the tribal elders who are turning to the government of Afghanistan for security and development." However, Tom Coghlan, the Telegraph reporter, came up with another, thought-provoking suggestion for the sudden lull in Taliban activity: a two weeks or so ago, the new opium poppy sowing season began.

In the meantime there are few signs that the wider, strategic battle for hearts and minds is being won. The UNHCR estimated this week that 90,000 Afghans have been displaced by the fighting in southern Afghanistan. And Reuters carried another interesting report about the Taliban's efforts to force schools in southern Afghanistan to close. It is a measure of just how deep the problem is that even the girl's schoool in the regional capital, Lashkar Gah, which is under British noses, has been threatened. The British have an uphill struggle ahead.